| Gastroenterology Research, ISSN 1918-2805 print, 1918-2813 online, Open Access |

| Article copyright, the authors; Journal compilation copyright, Gastroenterol Res and Elmer Press Inc |

| Journal website http://www.gastrores.org |

Review

Volume 4, Number 5, October 2011, pages 185-193

Criteria for Referring Patients With Outpatient Gastroenterological Disease for Specialist Consultation: A Review of the Literature

Carolyn De Costera, d, Monica Cepoiu-Martinb, Carla Nashc, Tom W Noseworthyb

aData Integration, Measurement & Reporting, Alberta Health Services, Canada

bDepartment of Community Health Sciences, Faculty of Medicine, University of Calgary, Calgary, Alberta, Canada

cDepartment of Internal Medicine, Faculty of Medicine, University of Calgary, Calgary, Alberta, Canada

dCorresponding author: Carolyn De Coster, Data Integration, Measurement and Reporting, Alberta Health Services, Northwest II, 4520-16thAvenue NW, Calgary, Alberta, T3B 0M6, Email:

Manuscript accepted for publication September 1, 2011

Short title: Criteria for GI Referral

doi: https://doi.org/10.4021/gr350w

| Abstract | ▴Top |

Background: Demands on gastroenterology are growing, as a result of the high prevalence of digestive diseases, the impact of colon cancer screening programs and an aging population. Prioritizing referrals to gastroenterology would assist in managing wait times. Our objectives were (1) to assess whether there were consistent criteria to guide referrals from family physicians for gastroenterological outpatient consultation and (2) to determine if there were different levels of urgency or priority in referral criteria.

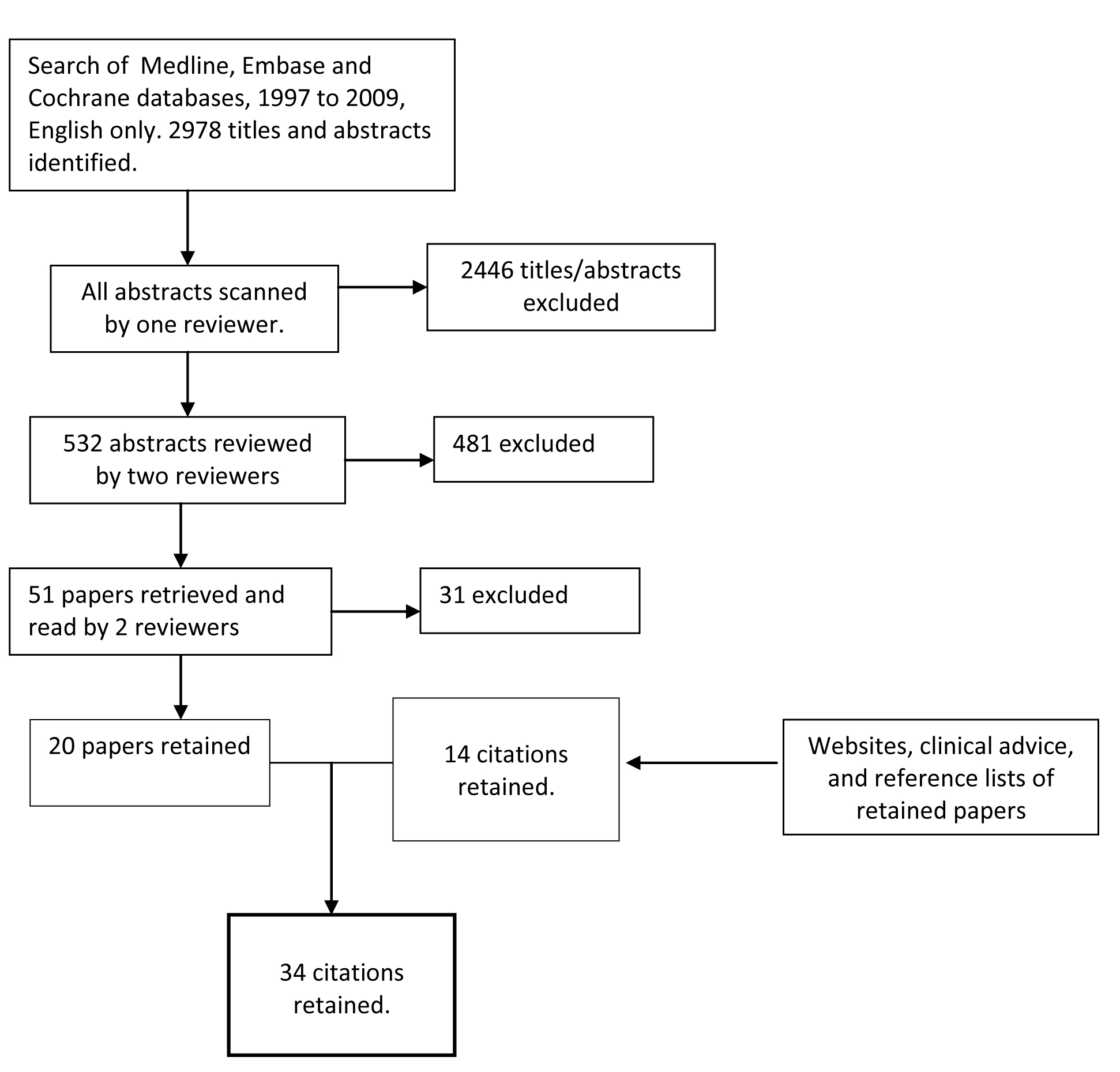

Methods: We conducted a scoping review, searching Medline, Embase and Cochrane databases from 1997 to 2009, using the terms referral, triage, consultation and at least one from a list of gastroenterology-specific search terms. Of 2978 initial results, 51 papers were retrieved, and 20 were retained after review by two reviewers. Additional publications were identified through hand searches of retained papers, website searches and nomination by a panel of specialists.

Results: Thirty-four papers, reports or websites were retained. No referral criteria covered the spectrum of disorders that might be referred by family physicians to gastroenterologists. Criteria for referral were most commonly listed for suspected colorectal cancer, followed by suspected upper GI cancer, hepatitis, and functional disorders.

Conclusions: A clinical panel comprised of gastroenterologists and primary care providers, informed by this literature review, are completing the work of formulating a Gastroenterology Priority Referral Score, and plan to test the reliability and validity of the tool for determining the relative urgency for referral from primary care to gastroenterology.

Keywords: Family physicians; Gastroenterology; Gastrointestinal diseases; Referral and consultation; Review

| Introduction | ▴Top |

Demands on gastroenterology are growing. Digestive cancers are the second leading cause of cancer deaths in Canada. Furthermore, Canada has the highest incidence of both gastrointestinal ulcers and inflammatory bowel disease in the world and the prevalence of medically diagnosed bowel disorders has doubled in the past decade [1]. International data reveal that Canada and the UK rank fourth and fifth, respectively, among five countries in terms of gastroenterologists per 100,000 population. It is projected that the number of gastroenterologists will fall by 15% in the next 10 years unless training positions are increased [2].

A 2005 audit of Canadian gastroenterologists revealed that median wait times from primary care referral to investigation were longer than consensus targets set by the Canadian Association of Gastroenterology for seven digestive diseases [3]. Of note, two conditions had two-week targets: high likelihood of cancer based on imaging or physical exam and significant active inflammatory bowel disease (IBD). The cancer median waiting time was relatively close to the target: 26 days (interquartile range (IQR) 8-56 days), but the median wait for active IBD far exceeded the target: 101 days (IQR 35-209 days).

It is important to remember that gastroenterologists deal with a number of conditions affecting the luminal digestive tract (oesophagus, stomach, intestines) as well as biliary tract disease, pancreas disorders, liver disease and functional disorders. Given the scope of gastroenterologic outpatient consultation and long waiting times, we scoped the literature to assess whether there were consistent criteria to guide referrals from primary care to specialist consultation usually provided by a gastroenterologist. Furthermore we explored whether there were different levels of urgency or priority in referral criteria. This paper describes the findings of the review.

| Materials and Methods | ▴Top |

Scoping reviews systematically synthesize a wide range of research and non-research material, identifying key concepts, sources of evidence and gaps in the research [4-5]. Steps in a scoping review are: identifying the research question, identifying relevant studies, study selection, charting the data, collating and summarizing the results and consultation [6-7].

An academic research librarian searched Medline, Embase and Cochrane databases from 1997 to 2009, English only, using the terms referral, triage, consultation AND at least one from a list of gastroenterology-specific search terms (see appendix, web only file). The list was reviewed by a gastroenterologist and included disease terms such as cholelithiasis, oesophageal cancer, liver cirrhosis, rectal cancer, ulcerative colitis, as well as a list of symptoms such as rectal bleeding or jaundice. The search yielded 2978 abstracts and titles (Fig. 1).

Click for large image | Figure 1. Diagram of literature search strategy for gastroenterology referral tool. |

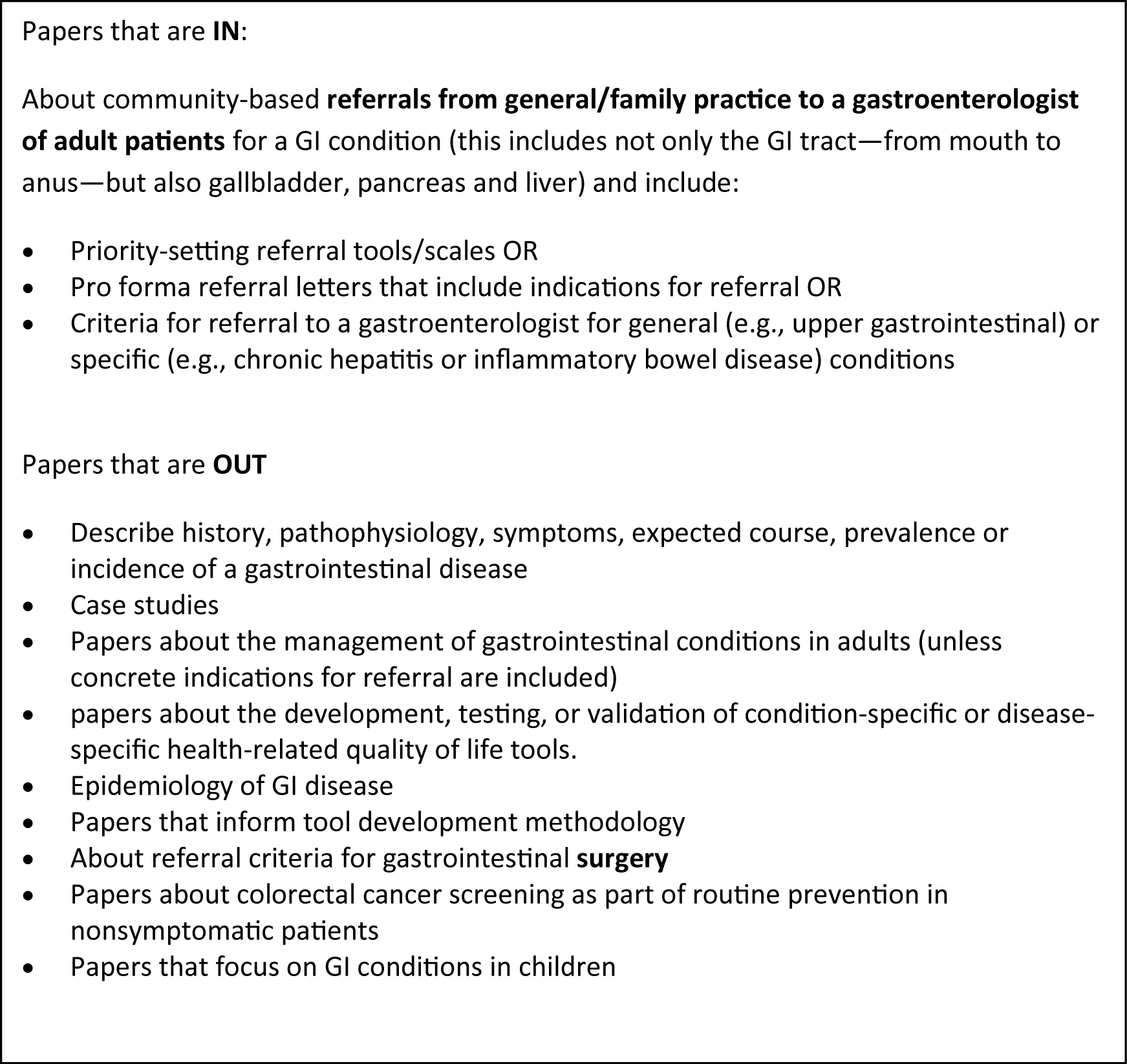

Criteria for the selection of relevant abstracts were developed, tested and revised in an iterative process. The inclusion and exclusion criteria are described in Fig. 2. In scoping reviews, breadth is important but practicalities, such as time, budget and personnel resources, are important as well [7]. We knew from previous experience that many of the papers would not be relevant, and because of time constraints, each abstract was screened initially by one reviewer to determine if it should go on to a second in-depth review, with the understanding among team members to be as broadly inclusive as possible; 2446 abstracts were excluded at this stage. All remaining abstracts/titles were reviewed by at least two reviewers and rated as Yes, No or Possible. Abstracts or titles rated by at least one reviewer as Yes or Possible were reviewed by a third person. At the end of this process 51 papers had been identified for retrieval. These 51 papers were read in full by two reviewers; conflicts were read by a third reviewer and then discussed by all three readers. Twenty papers remained after this step.

Click for large image | Figure 2. Inclusion and exclusion criteria. |

References were hand-searched to identify any further citations. As well websites were consulted to look for referral prioritization guidelines or tools, including gastroenterology societies of Canada, Europe, Australia, United Kingdom and United States. This step yielded 12 additional citations. One reviewer abstracted the relevant data from each retained reference and compiled the results. In the consultation step, the resulting report was reviewed by five practising gastroenterologists who nominated two additional papers for inclusion. Thus 34 references were included in this systematic review.

| Results | ▴Top |

Despite the high number of initial abstracts identified in our search, relatively few papers were retained. Table 1 identifies the 34 retained papers, reports or websites [8-41]. Criteria for referral were most commonly listed for suspected colorectal cancer[8, 10, 12, 13, 15-20, 22, 23, 25, 27, 28, 30, 31, 33, 35, 36, 38, 40]. Other GI conditions for which some referral criteria were found included suspected upper GI cancer[9, 24, 25, 27-30, 38, 39], hepatitis[11, 14, 26, 30], and functional disorders such as irritable bowel syndrome, dyspepsia, diarrhoea and constipation[21, 30, 32, 34, 37]. We found four papers on the management of a variety of important GI conditions, but they did not contain criteria for referral: inflammatory bowel disease[42], pancreatitis [43-44] and acute gastrointestinal blood loss[45]. The latter two require urgent hospitalization and would not go into the queue for outpatient gastroenterology consultation.

Click to view | Table 1. List of Retained References with Referral Criteria for Colorectal Cancer, Upper Gastrointestinal Cancer, Hepatitis and Functional Bowel Disease |

Colorectal Cancer

In Canada, colorectal cancer is the third leading type of cancer [46]. Its primary symptoms – rectal bleeding, changes in bowel habit, abdominal pain, weight loss, unexplained anaemia – are common to many benign colorectal diseases, thus making it a challenge for family physicians to select patients who need referral for a gastroenterology consultation and for specialists to assess urgency [10]. Several efforts have therefore been made to identify alarm symptoms[8, 13, 15, 35, 38, 40], which typically include rectal bleeding with a change in bowel habit to looser or more frequent stools, older age and rectal bleeding without anal symptoms (i.e., soreness, discomfort, itching, lumps, prolapse, and pain), older age and change in bowel habit to looser or more frequent stools, palpable right-sided abdominal or rectal mass, and iron deficiency anaemia [38]. While there appears to be agreement that older age is an important consideration in assessing the probability of colorectal cancer, there is some disagreement about what age is relevant, with reported ranges from 45 to 65 years[13, 15, 38, 40].

In a systematic literature review, Moayyedi et al. [25] found no data on the overall accuracy of alarm features in detecting colorectal cancer. Pooled sensitivity, specificity and likelihood ratios and their 95% confidence intervals were estimated from the relevant papers for symptoms of rectal bleeding, change in bowel habit, diarrhoea, constipation, weight loss, anaemia and abdominal pain. Pooled positive likelihood ratios were highest for weight loss (2.42) and unexplained anaemia (2.36), followed by rectal bleeding (1.66), change in bowel habit (1.28). Positive likelihood ratios were low for diarrhoea (0.93), constipation (0.69) and abdominal pain (0.69).

Several authors suggested that combinations of two or more symptoms increases the level of urgency [12, 17, 22, 33, 36] Lawrenson et al. [22] pointed out that the absolute risk of colorectal cancer for patients presenting with a combination of two symptoms (anaemia and rectal bleeding, anaemia and changes in bowel habit, or rectal bleeding and changes in bowel habit) is about twice as high as those with any single symptom. In a prospective study of 8529 patients referred to a surgical clinic over a 12-year period, Thompson et al. [36] evaluated change in bowel habit, rectal bleeding, abdominal pain and perianal symptoms along with age as predictors of colorectal cancer. The highest positive predictive values were found with rectal bleeding and change in bowel habit, especially in the absence of perianal symptoms (19.7%). Perianal symptoms were protective, while abdominal pain was neither predictive nor protective. These findings were also correlated with age, suggesting that age in combination with the presence or absence of these three symptoms could guide practitioners in determining who should be referred more urgently. John et al. [20] validated an electronic referral protocol (e-RP) which assigned an urgency level depending on patient age, medical history and cluster of symptoms. The e-RP seemed to perform better than physician assessment at assigning urgency level and had the potential to reduce the rate of emergency presentation of colorectal cancer from 16% to 9%.

The use of high-risk symptoms and signs as criteria for urgent referrals has led to overwhelming referral rates in the UK. In 2002, Selvachandran et al. [31] evaluated the sensitivity and specificity of the Patient Consultation Questionnaire. This questionnaire was designed to obtain a comprehensive clinical history and included the following factors: age and sex, blood per rectum, change in bowel habit, tenesmus, urgency, and incomplete emptying, perianal symptoms, abdominal symptoms, weight loss, loss of appetite, tiredness, family history and relevant medical history. This questionnaire produces a Weighted Numerical Score (WNS). The researchers determined that a WNS over 60 is the best criteria to prioritize patients with colorectal symptoms. At this cut-off point, the population urgently referred includes not only patients with cancers but also patients with benign diseases that need urgent management, such as ulcerative colitis and polyps. The use of this questionnaire has been supported by others[18, 47]. An evaluation of the WNS compared with several other tools [13, 15, 23, 35, 40] concluded that the WNS with a threshold of 50 had a comparable sensitivity but a higher specificity than the rest of the tools in detecting cancer, yielding the lowest referral rate. Moreover, the WNS enabled the prioritization of other relatively severe colorectal diseases.

Upper Gastrointestinal Cancer

The UK Department of Health’s [9, 38] two-week referral rule for suspected upper GI cancer includes: dysphagia, jaundice, upper abdominal pain, dyspepsia combined with alarm symptoms (weight loss, anaemia, vomiting), high-risk features in age 55+ (onset less than one year ago, or continuous symptoms since onset), or risk factors (family history of upper GI cancer in more than two first degree relatives, Barrett’s oesophagus, pernicious anaemia, peptic ulcer surgery more than 20 years ago, known dysplasia, atrophic gastritis or intestinal metaplasia).

These criteria lack both sensitivity and specificity: they would identify only 72% of cancer patients at their first visit to a GP, but result in many urgent referrals for upper GI endoscopy, most of whom will be found to have benign disease [29]. One chart audit on 396 patients referred with dysphagia found that 15% (60/396) of them did not have dysphagia, and 10% (41/396) were found to have cancer. Negative predictors of cancer were the presence of heartburn and having dysphagia for more than one year [24]. Another study concluded that alarm symptoms, defined as weight loss, dysphagia or melena/haematemesis, had a 4% positive predictive value for finding cancer, but that many patients with cancer identified using these guidelines are untreatable [39].

General Non-Cancer Referrals

Beyond cancer, there are many reasons for referral to gastroenterology from primary care, with varying degrees of urgency for referral. Much of the literature focuses on specific diseases. The Guidelines for referral of patients with chronic Hepatitis B (HBV) were developed and evaluated in Rotterdam. The Dutch standard was for family physicians to refer all patients with chronic HBV to a specialist [26]. However the evaluation demonstrated that the guidelines enabled family physicians to select only those patients with chronic active HBV for specialist referral, thus avoiding referrals for chronic inactive infection since no treatment was indicated for these patients. This is in contrast to the Canadian consensus which recommends that patients with chronic viral hepatitis should be seen within two months, largely because of patient anxiety [30].

In 1998, Fallon recommended that all patients newly diagnosed with hepatitis C should be referred to a specialist, except for those with undetectable HCV RNA levels, an indication of spontaneous recovery [14]. More recently, the Dublin Area Hepatitis C Initiative Group created criteria to help predict which patients with hepatitis C from drug use would benefit from therapy [11]. These criteria include HCV and PCR/phenotype testing, clinical and laboratory evaluation of liver status, freedom from unstable drug use, psychiatric history and social stability.

Inflammatory bowel disease (IBD) includes ulcerative colitis and Crohn’s disease. The most common symptom of ulcerative colitis is bloody diarrhoea; less common are colicky abdominal pain, urgency and tenesmus [42]. Crohn’s disease symptoms include abdominal pain, diarrhoea, weight loss, malaise, anorexia and fever. Although we found guidelines for the management of patients with IBD, there were no criteria for referral. A vexing problem is distinguishing between IBD with its morbidity and need for optimal therapy, from functional bowel disorders.

Functional bowel disorders, such as irritable bowel syndrome, dyspepsia and chronic constipation, are the most common medical conditions seen in both primary care and gastroenterology [48]. The prevalence of IBS ranges from 2.5% to 20%, depending on the criteria set used [32]. The Rome III diagnostic criteria are the most up-to-date: recurrent abdominal pain or discomfort at least 3 days a month in the past 3 months, associated with two or more of the following: improvement with defecation, onset associated with a change in frequency of stool, or onset associated with a change in appearance of stool [41]. Referral for IBS should occur if symptoms are atypical or alarming (such as age 50 or older, short history of symptoms, documented weight loss, nocturnal symptoms, male sex, family history of colon cancer, anaemia, rectal bleeding, recent antibiotic use), if there is uncertainty about the diagnosis, or if patient concerns have not been successfully allayed in the primary care physician visit [21, 32].

In patients with dyspepsia, Tytgat et al. [37] summarized risk factors that should prompt the referral of these patients for early endoscopy: the presence of alarm symptoms (anaemia or evidence of bleeding, severe or persistent pain, painful swallowing, difficulty swallowing, recurrent or persistent vomiting, anorexia, weight loss); presentation with first-time dyspepsia or altered symptoms over the age of 55; previous history of peptic ulcer disease; current ulcer disease and recent evidence of substantial gastrointestinal bleeding; use of NSAIDs; and other risk factors (heavy smoking, alcohol abuse). Reflux-like symptoms (regurgitation, reflux or heartburn) have been shown to have a 33% positive predictive value for finding reflux oesophagitis during open-access endoscopy [39].

| Discussion | ▴Top |

Our review of the literature did not elucidate any tools or guidelines that would prioritize the broad scope of patients that may be referred by primary care physicians to gastroenterologists. There appears to be some consensus about alarm symptoms that should prompt an urgent referral. For lower GI conditions, these include rectal bleeding, anaemia and change in bowel habit, especially if at least two of these symptoms are present at the same time. For upper GI disease, they are progressive dysphagia, haematemesis, or dyspepsia with weight loss or anaemia or vomiting. Using these criteria to designate patients as urgent could result in overwhelming gastroenterological services; even though most patients thus referred will have benign disease, it is important that patients have reasonable access for specialist evaluation when referral is indicated. Managing the queue is a challenge for many gastroenterology practices.

In Canada, colorectal cancer is the second leading cause of cancer deaths in males and third in females [46]. Earlier detection through screening programs or referral guidelines thus has the potential to save many lives. When the UK implemented its two-week-wait rule for consultations for patients with alarm symptoms, many GI practices were overwhelmed. The literature demonstrates that combinations of symptoms increase the likelihood of cancer detection, suggesting that combinations of symptoms, together with age, should be incorporated into referral guidelines and may help in assessing urgency.

In 2006, a Consensus Group of Canadian gastroenterologists and hepatologists published medically acceptable wait times for access to specialist gastroenterological care [30]. Four urgency categories were defined: within 24 hours, within 2 weeks, within 2 months and within 6 months. Each category lists from 4 to 10 symptoms or conditions. This work goes some distance towards identifying urgency criteria spanning the scope of referrals. However, its four urgency bands are relatively broad. Furthermore, each wait time target can be met by the presence of only one condition or symptom, and does not allow for the additional urgency that may be implied by the presence of a constellation of symptoms.

Development of a prioritization referral tool would benefit both primary care providers and gastroenterologists. For primary care providers, the tool would help to standardize the referral process, reducing the frustration of multiple forms and referral requirements. It should be easy to use, and if tests are to be performed, they should not be expensive, complicated, or restricted to specialist use [49]. For gastroenterologists, required information will be available; studies show that 50% or more of referral letters are missing information that specialists require [50-54]. Referrals would be prioritized in order of urgency in a transparent process. To this end, a clinical panel comprised of gastroenterologists and primary care providers, informed by this literature review, are completing the work of formulating a Gastroenterology Priority Referral Score, and plan to test the reliability and validity of the tool for determining the relative urgency for referral from primary care to gastroenterology.

Acknowledgments

This work was funded by Alberta Health and Wellness – Access to Medical Services Grant. We thank Diane Lorenzetti, Barbara Conner-Spady and Rithesh Ram for their help in conducting the search and reviewing abstracts.

| References | ▴Top |

- Canadian Digestive Health Association. Statistics. http://www.cdhf.ca/digestive-disorders/statistics.shtml. Accessed 02 Jun 2011.

- Moayyedi P, Tepper J, Hilsden R, Rabeneck L. International comparisons of manpower in gastroenterology. Am J Gastroenterol. 2007;102(3):478-481.

pubmed doi - Leddin D, Armstrong D, Barkun AN, Chen Y, Daniels S, Hollingworth R, Hunt RH,

et al . Access to specialist gastroenterology care in Canada: comparison of wait times and consensus targets. Can J Gastroenterol. 2008;22(2):161-167.

pubmed - Davis K, Drey N, Gould D. What are scoping studies? A review of the nursing literature. Int J Nurs Stud. 2009;46(10):1386-1400.

pubmed doi - Canadian Institutes of Health Research. Knowledge Synthesis Grant 2011-2012. http://www.researchnetrecherchenet.ca. Accessed 22 Jul 2011.

- Arksey H, O'Malley L. Scoping studies: Towards a methodological framework. Int J Social Research Methodology. 2005;8:19-32.

- Levac D, Colquhoun H, O'Brien KK. Scoping studies: advancing the methodology. Implement Sci. 2010;5:69.

pubmed - ACPGBI. Guidelines for the Management of Colorectal Cancer, 3rd edition. London: Association of Coloproctology of Great Britain and Ireland, 2007.

- Allum WH, Griffin SM, Watson A, Colin-Jones D. Guidelines for the management of oesophageal and gastric cancer. Gut. 2002;50(Suppl 5):v1-23.

pubmed - Baig MK, Marks CG. Referral guidelines for colorectal cancer: a threat or a challenge?. Hosp Med. 2000;61(7):452-453.

pubmed - Barry J, Bourke M, Buckley M, Coughlan B, Crowley D, Cullen W, Dooley S,

et al . Hepatitis C among drug users: consensus guidelines on management in general practice. Ir J Med Sci. 2004;173(3):145-150.

pubmed doi - Barwick TW, Scott SB, Ambrose NS. The two week referral for colorectal cancer: a retrospective analysis. Colorectal Dis. 2004;6(2):85-91.

pubmed doi - Davies RJ, Ewings P, Welbourn R, Collins C, Kennedy R, Royle C. A prospective study to assess the implementation of a fast-track system to meet the two-week target for colorectal cancer in Somerset. Colorectal Dis. 2002;4(1):28-30.

pubmed doi - Fallon HJ. Chronic hepatitis C: When to refer. Consultant. 1998;38:1998.

- Fijten GH, Starmans R, Muris JW, Schouten HJ, Blijham GH, Knottnerus JA. Predictive value of signs and symptoms for colorectal cancer in patients with rectal bleeding in general practice. Fam Pract. 1995;12(3):279-286.

pubmed doi - Hamilton W, Sharp D. Diagnosis of colorectal cancer in primary care: the evidence base for guidelines. Fam Pract. 2004;21(1):99-106.

pubmed doi - Harinath G, Somasekar K, Haray PN. The effectiveness of new criteria for colorectal fast track clinics. Colorectal Dis. 2002;4(2):115-117.

pubmed doi - Hodder RJ, Ballal M, Selvachandran SN, Cade D. Pitfalls in the construction of cancer guidelines demonstrated by the analyses of colorectal referrals. Ann R Coll Surg Engl. 2005;87(6):419-426.

pubmed doi - Jiwa M, Arnet H, Bulsara M, Ee HC, Harwood A. What is the importance of the referral letter in the patient journey? A pilot survey in Western Australia. Qual Prim Care. 2009;17(1):31-36.

pubmed - John SK, George S, Howell RD, Primrose JN, Fozard JB. Validation of the lower gastrointestinal electronic referral protocol. Br J Surg. 2008;95(4):506-514.

pubmed doi - Jones J, Boorman J, Cann P, Forbes A, Gomborone J, Heaton K, Hungin P,

et al . British Society of Gastroenterology guidelines for the management of the irritable bowel syndrome. Gut. 2000;47(Suppl 2):ii1-19.

pubmed - Lawrenson R, Logie J, Marks C. Risk of colorectal cancer in general practice patients presenting with rectal bleeding, change in bowel habit or anaemia. Eur J Cancer Care (Engl). 2006;15(3):267-271.

pubmed doi - Majumdar SR, Fletcher RH, Evans AT. How does colorectal cancer present? Symptoms, duration, and clues to location. Am J Gastroenterol. 1999;94(10):3039-3045.

pubmed doi - Melleney EM, Subhani JM, Willoughby CP. Dysphagia referrals to a district general hospital gastroenterology unit: hard to swallow. Dysphagia. 2004;19(2):78-82.

pubmed doi - Moayyedi P, Rabeneck L, Hilsden R, Leddin D, Barkun A, Velduhzen van Zanten S. An Evidence-Based Assessment of Appropriate Waiting Times for Gastrointestinal Cancers [final report]. Ottawa: Canadian Institutes of Health Research. 2006.

- Mostert MC, Richardus JH, de Man RA. Referral of chronic hepatitis B patients from primary to specialist care: making a simple guideline work. J Hepatol. 2004;41(6):1026-1030.

pubmed doi - Newton JL. Care of the elderly with gastrointestinal problems in family practice. Best Pract Res Clin Gastroenterol. 2001;15(6):1013-1025.

pubmed doi - McKie C, Ahmad UA, Fellows S, Meikle D, Stafford FW, Thomson PJ, Welch AR,

et al . The 2-week rule for suspected head and neck cancer in the United Kingdom: referral patterns, diagnostic efficacy of the guidelines and compliance. Oral Oncol. 2008;44(9):851-856.

pubmed doi - Panter SJ, Bramble MG, O'Flanagan H, Hungin AP. Urgent cancer referral guidelines: a retrospective cohort study of referrals for upper gastrointestinal adenocarcinoma. Br J Gen Pract. 2004;54(505):611-613.

pubmed - Paterson WG, Depew WT, Pare P, Petrunia D, Switzer C, Veldhuyzen van Zanten SJ, Daniels S. Canadian consensus on medically acceptable wait times for digestive health care. Can J Gastroenterol. 2006;20(6):411-423.

pubmed - Selvachandran SN, Hodder RJ, Ballal MS, Jones P, Cade D. Prediction of colorectal cancer by a patient consultation questionnaire and scoring system: a prospective study. Lancet. 2002;360(9329):278-283.

pubmed doi - Spiller R, Aziz Q, Creed F, Emmanuel A, Houghton L, Hungin P, Jones R,

et al . Guidelines on the irritable bowel syndrome: mechanisms and practical management. Gut. 2007;56(12):1770-1798.

pubmed doi - Tan YM, Rosmawati M, Ranjeev P, Goh KL. Predictive factors by multivariate analysis for colorectal cancer in Malaysian patients undergoing colonoscopy. J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2002;17(3):281-284.

pubmed doi - Thomas PD, Forbes A, Green J, Howdle P, Long R, Playford R, Sheridan M,

et al . Guidelines for the investigation of chronic diarrhoea, 2nd edition. Gut. 2003;52(Suppl 5):v1-15.

pubmed - Thompson MR, Heath I, Ellis BG, Swarbrick ET, Wood LF, Atkin WS. Identifying and managing patients at low risk of bowel cancer in general practice. BMJ. 2003;327(7409):263-265.

pubmed doi - Thompson MR, Perera R, Senapati A, Dodds S. Predictive value of common symptom combinations in diagnosing colorectal cancer. Br J Surg. 2007;94(10):1260-1265.

pubmed doi - Tytgat G, Hungin AP, Malfertheiner P, Talley N, Hongo M, McColl K, Soule JC,

et al . Decision-making in dyspepsia: controversies in primary and secondary care. Eur J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 1999;11(3):223-230.

doi pubmed - Department of Health. Guidelines for urgent referral of patients with suspected cancer [wallchart]. http://www.dh.gov.uk/en/Publicationsandstatistics/. Accessed 22 Oct 2008.

- van Kerkhoven LA, van Rijswijck SJ, van Rossum LG, Laheij RJ, Witteman EM, Tan AC, Jansen JB. Is there any association between referral indications for open-access upper gastrointestinal endoscopy and endoscopic findings?. Endoscopy. 2007;39(6):502-506.

pubmed doi - Wirral Hospital NHS Trust. Suspected Bowel Cancer - Referrals Only. Merseyside, UK: The Trust, 2001.

- Longstreth GF, Thompson WG, Chey WD, Houghton LA, Mearin F, Spiller RC. Functional bowel disorders. Gastroenterology. 2006;130(5):1480-1491.

pubmed doi - Carter MJ, Lobo AJ, Travis SP. Guidelines for the management of inflammatory bowel disease in adults. Gut. 2004;53(Suppl 5):V1-16.

pubmed - Hirota M, Takada T, Kawarada Y, Hirata K, Mayumi T, Yoshida M, Sekimoto M,

et al . JPN Guidelines for the management of acute pancreatitis: severity assessment of acute pancreatitis. J Hepatobiliary Pancreat Surg. 2006;13(1):33-41.

pubmed doi - UK Working Party on Acute Pancreatitis. UK guidelines on the management of acute pancreatitis. Gut 2005;54:1-9..

- Palmer K, Nairn M. Management of acute gastrointestinal blood loss: summary of SIGN guidelines. BMJ. 2008;337:a1832.

pubmed - Canadian Cancer Society. Canadian Cancer Statistics 2010 [powerpoint]. http://www.cancer.ca/Canada-wide/. Accessed 16 Jul 2010.

- Vella M, O'Dwyer PJ. Prediction of colorectal cancer by consultation questionnaire. Lancet. 2002;360(9350):2079-2080, author reply 2080.

pubmed doi - Chang L. Review article: epidemiology and quality of life in functional gastrointestinal disorders. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2004;20(Suppl 7):31-39.

pubmed - Rudwaleit M, van der Heijde D, Khan MA, Braun J, Sieper J. How to diagnose axial spondyloarthritis early. Ann Rheum Dis. 2004;63(5):535-543.

pubmed doi - Garasen H, Johnsen R. The quality of communication about older patients between hospital physicians and general practitioners: a panel study assessment. BMC Health Serv Res. 2007;7:133.

pubmed - Jiwa M, Coleman M, McKinley RK. Measuring the quality of referral letters about patients with upper gastrointestinal symptoms. Postgrad Med J. 2005;81(957):467-469.

pubmed doi - Samanta A, Roy S. Referrals from general practice to a rheumatology clinic. Br J Rheumatol. 1988;27(1):74-76.

pubmed doi - Speed CA, Crisp AJ. Referrals to hospital-based rheumatology and orthopaedic services: seeking direction. Rheumatology (Oxford). 2005;44(4):469-471.

pubmed doi - Ong SP, Lim LT, Barnsley L, Read R. General practitioners' referral letters—Do they meet the expectations of gastroenterologists and rheumatologists?. Aust Fam Physician. 2006;35(11):920-922.

pubmed

This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License, which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited.

Gastroenterology Research is published by Elmer Press Inc.