| Gastroenterology Research, ISSN 1918-2805 print, 1918-2813 online, Open Access |

| Article copyright, the authors; Journal compilation copyright, Gastroenterol Res and Elmer Press Inc |

| Journal website https://www.gastrores.org |

Case Report

Volume 15, Number 4, August 2022, pages 217-224

Flood Syndrome

Jia Li Leea, c, Jeffrey Jiangb

aDepartment of Family Medicine, National University Health System Singapore, Singapore 119228, Singapore

bMedical Department, St Luke’s Hospital, Singapore 659674, Singapore

cCorresponding Author: Jia Li Lee, Department of Family Medicine, National University Health System Singapore, Singapore 119228, Singapore

Manuscript submitted February 8, 2022, accepted June 20, 2022, published online August 23, 2022

Short title: Flood Syndrome

doi: https://doi.org/10.14740/gr1508

| Abstract | ▴Top |

Flood syndrome refers to the exsanguination of ascitic fluid following the spontaneous rupture of an umbilical hernia, and is a rare complication of liver cirrhosis with ascites. In this case report, we describe a 67-year-old patient with Flood syndrome who was initially managed conservatively in a community hospital run by primary care physicians, prior to transfer to a tertiary hospital for specialist surgical review and management. We also performed a literature review of the current treatment modalities to manage this condition.

Keywords: Flood syndrome; Spontaneous umbilical hernia rupture; Liver cirrhosis

| Introduction | ▴Top |

Approximately 20% of patients with ascites eventually develop umbilical hernias as a result of raised intra-abdominal pressure, weakening of anterior abdominal wall muscles from poor nutrition [1, 2], and supraumbilical fascial defect due to possible recanalization of the umbilical vein secondary to portal hypertension [3].

Flood syndrome was first described by Johnson in 1901 and the term was coined by Frank B. Flood in 1961 [4]. It is a rare complication of liver cirrhosis with ascites and is frequently (> 75%) preceded by cutaneous infection and/or skin necrosis or ulceration and precipitated by raised intra-abdominal pressure [5], which includes vomiting, coughing, and straining with defecation [6].

It is important to recognize Flood syndrome as complications such as bowel incarceration, hemodynamic instability, electrolyte abnormalities and infection including cellulitis and peritonitis [7] can arise, amounting to a mortality rate of 30% [8]. This case report describes the progress and management of a patient with Flood syndrome admitted to a community hospital.

| Case Report | ▴Top |

The patient is a 67-year-old Chinese male with a past medical history of Child’s C11 MELD 18 alcoholic liver cirrhosis, diagnosed in 2008, complicated by ascites with previous paracentesis (August 2019), esophageal varices, splenomegaly with anemia and thrombocytopenia, hepato-renal syndrome and a reducible umbilical hernia. He did not have any other significant medical conditions. His significant medications include propranolol 5 mg every morning, frusemide 20 mg every morning, spironolactone 75 mg every morning, omeprazole 20 mg twice a day and lactulose 10 mL every morning.

He was admitted to an acute hospital for Klebsiella bacteremia secondary to a perianal abscess and was treated with intravenous antibiotics and an incision and drainage of the abscess. He also underwent abdominal paracentesis in September 2020 for worsening ascites which was causing abdominal discomfort. This was his second paracentesis since he was diagnosed with liver cirrhosis. During this admission, he was also noted to have hepatorenal syndrome - acute kidney injury (serum creatinine rose from 68 to 198 µmol/L) which responded well to terlipressin and intravenous albumin. He was then transferred to a community hospital for stepdown care for his perianal wound management.

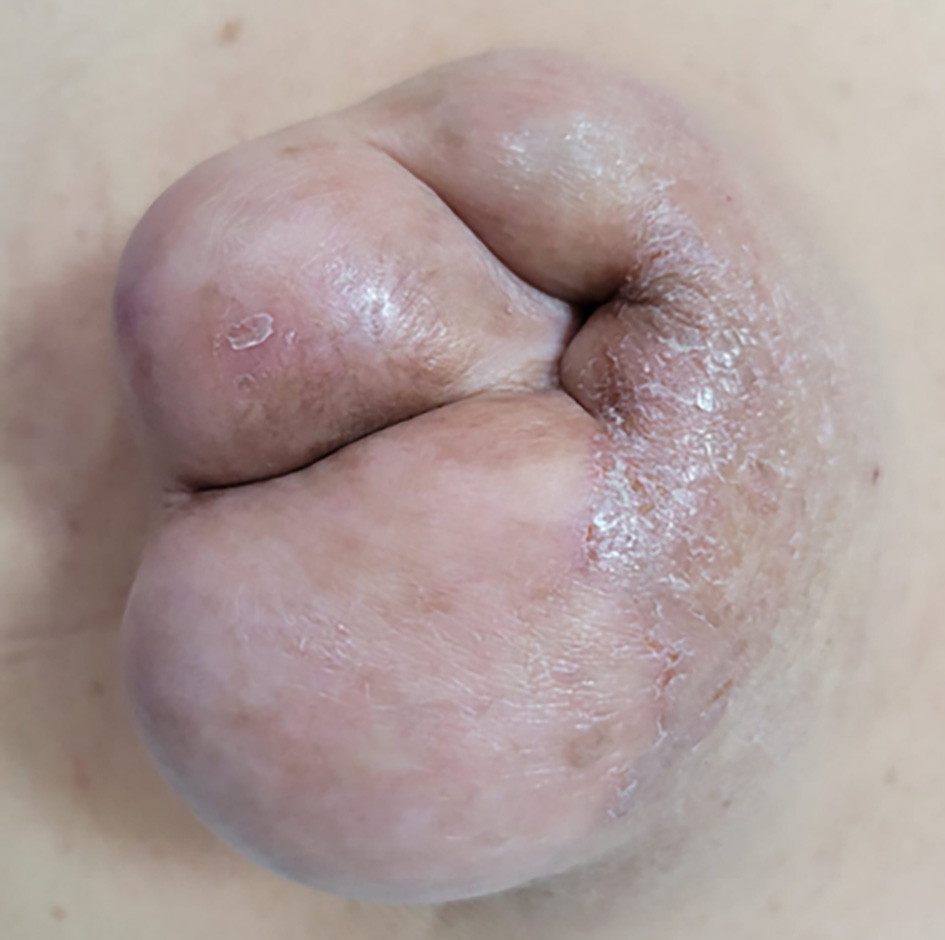

Physical examination revealed a soft and non-tender abdomen that was distended. Shifting dullness and fluid thrill were demonstrated. There was a 4-cm reducible and non-tender umbilical hernia that was not incarcerated nor strangulated. The hernia had a superficial ulcer but did not have any bleeding or pus (Fig. 1). The perianal wound was granulating well and clean. He was otherwise hemodynamically stable and had no signs of hepatic encephalopathy or sepsis.

Click for large image | Figure 1. Ulcerated umbilical hernia. |

During his third week of admission to the community hospital, the patient reported a spontaneous leakage of straw-colored fluid from his umbilical hernia. On examination, there was copious amounts of ascitic fluid extruding from the ruptured skin of the umbilical hernia which developed at the ulcer site (Fig. 2). The clinical diagnosis was Flood syndrome. He was initially managed with compressive gauze but a urostomy bag (Fig. 3) was subsequently utilized in view of high volume of output (estimated 1 L per day).

Click for large image | Figure 2. Ascitic fluid leaking from a ruptured umbilical hernia, being held up by staff wearing blue gloves. |

Click for large image | Figure 3. Urostomy bag utilized to monitor ascitic fluid output from Flood syndrome. |

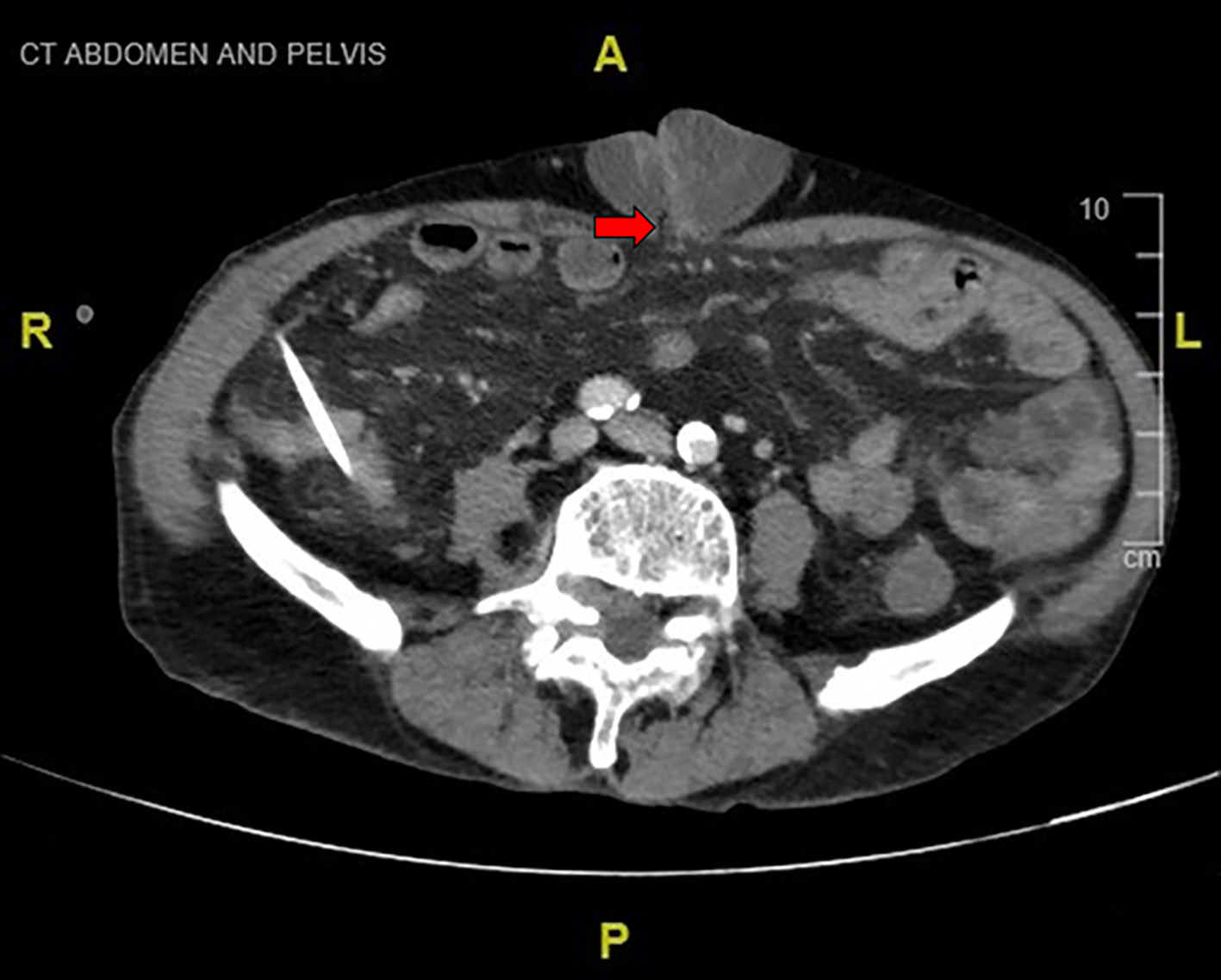

A computed tomography (CT) scan of his abdomen prior to his transfer to the hospital already revealed generalized ascites and a large hernia with a small abdominal-cutaneous tract forming (Fig. 4). Blood tests performed did not reveal any acute drop in hemoglobin from his baseline. The hemoglobin level was 10.8 g/dL, total white count was 6.34 × 109/L, platelet count was 65 × 109/L, serum creatinine was 68 µmol/L, estimated glomerular filtration rate (eGFR) was 94 mL/min, sodium was 132 mmol/L, potassium was 5.0 mmol/L, urea was 7.2 mmol/L, albumin was 27 g/L, total bilirubin was 57 µmol/L, aspartate transaminase was 80 U/L, alanine transaminase was 30 U/L, alkaline phosphatase was 134 U/L and international normalized ratio (INR) was 1.28.

Click for large image | Figure 4. CT scan of abdomen revealing an umbilical hernia with a small abdominal-cutaneous tract forming (red arrow). CT: computed tomography. |

In view of the persistently high output from the umbilical hernia, the patient was transferred back to the acute hospital for surgical review and management. In view of the large size of the hernia, the patient was not suitable for bedside hernia repair. He was offered hernia repair under general anesthesia and transjugular intrahepatic portosystemic shunting (TIPS) but he declined the procedures in view of the risks. The patient was thus treated conservatively with optimization of spironolactone and furosemide and given intravenous albumin infusions. Paracentesis performed drained about 2.5 L during his 5 days of hospital admission. He was also started on oral ciprofloxacin for spontaneous bacterial peritonitis prophylaxis. Eventually after 5 days of inpatient treatment, he was discharged with the colostomy bag and for outpatient wound care at the community hospital’s outpatient clinic.

During follow-up review about 11 months later, the patient continued to be drinking half to one bottle of red wine daily. He had no re-hospitalizations and his umbilical hernia wound had healed with no recurrence of ascitic fluid leakage (Fig. 5). At the time of submission of the article, the patient underwent three previous paracenteses and did not require further therapeutic paracentesis after discharge nor re-hospitalization.

Click for large image | Figure 5. Healed umbilical hernia wound (11 months after hospital discharge). |

| Discussion | ▴Top |

Flood syndrome refers to the exsanguination of ascitic fluid following the spontaneous rupture of an umbilical hernia. Due to the rarity of this condition, there is no standardized treatment protocol [9], with current literature being limited to case reports or case series (Table 1 [1-27]). Table 1 describes the interventions and various outcomes observed based on information obtained from case reports and case series published in the literature.

Click to view | Table 1. Summary of Management of Cases of Flood Syndrome Published in the Literature |

Treatment of Flood syndrome typically begins with fluid resuscitation and antibiotics [6], wound care such as sterile occlusive dressing application [10] or placement of an ostomy pouch [1]. Non-invasive management also includes nutritional optimization, antibiotics, avoiding hepatotoxic medications [8].

This is followed by consideration of methods for reducing ascitic pressure on the hernia wound, and hernia defect repair including use of fibrin glue [26, 27] or umbilical herniorrhaphy (either elective after medical optimization or emergency) [1].

Ascitic management includes alcohol abstinence in alcohol-related cirrhosis, restriction of sodium intake (80 - 120 mmol per day), diuretics (aldosterone antagonists, loop diuretics and amiloride) with close monitoring of electrolytes and renal function and paracentesis (large volume paracentesis with albumin infusion to prevent circulatory dysfunction) [12, 28]. In patients with refractory ascites, treatment options include large volume paracentesis with albumin, diuretic treatment, peritoneovenous shunting (PVS), insertion of transjugular intrahepatic portosystemic shunt and consideration of liver transplantation [28].

TIPS involves the creation of a low resistance communication between the high-pressure intrahepatic branch of the portal vein and low-pressure hepatic vein under angiographic guidance, thereby reducing portal pressure and ascites. TIPS also has beneficial effects on the cardiovascular system, renal function, nitrogen balance and body weight. However, it is associated with complications including hepatic encephalopathy, shunt thrombosis and stenosis. Moreover, it is not suitable in patients with severe liver disease (serum bilirubin > 5 mg/dL, INR > 2 or Child-Pugh score > 11, current hepatic encephalopathy ≥ grade 2 or chronic hepatic encephalopathy) or severe extrahepatic conditions.

Deciding on subsequent treatment is difficult as supportive management is associated with a mortality rate of more than 60% [11], while surgical management involves high postoperative morbidity of up to 71% [3] and mortality of 20-60% [4], although immediate surgical intervention reduces the morality to 6-20% [1]. Thus, in suitable patients, umbilical herniorrhaphy without mesh is recommended and should be followed by ascites control [29] as mentioned above. The repair is ideally performed after medical optimization [8] unless in emergency situations such as peritonitis [13], bowel incarceration or evisceration [14]. This is to minimize postoperative complications which include wound infection or dehiscence, ascitic fluid leakage, liver failure, bleeding, ileus, encephalopathy and hernia recurrence [1, 15]. Umbilical hernia repair should not be performed in patients with a patent umbilical vein due to risks of portal venous thrombosis and acute liver failure [16].

In the primary care setting, the prevention of umbilical hernia rupture can be achieved by optimizing ascites management with the use of diuretics, and avoidance of alcohol and non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs and angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitors, and the cautionary use of other medications such as alpha-1 adrenergic receptor antagonists, dipyridamole and certain antibiotics [28]. Patients would also benefit from education on the complications of cirrhosis, good skin care and given advice on dietary salt and fluid restriction [1, 15].

Conclusion

Flood syndrome is a rare complication of liver cirrhosis with ascites which carries a high mortality rate. In the community hospital setting with no access to the surgical team, management options include medical therapy and local wound care. Primary care physicians can play a role in the prevention of umbilical hernia rupture with optimization of ascites management.

Acknowledgments

None to declare.

Financial Disclosure

There was no specific funding source to be mentioned.

Conflict of Interest

The authors have no conflict of interest to declare.

Informed Consent

Written informed consent has been obtained from the patient for the publication of the case report and the relevant clinical information.

Author Contributions

Jia Li Lee contributed to the writing and editing of the manuscript. Jeffrey Jiang was the mentor and contributed to the design and critical revision of the manuscript.

Data Availability

The authors declare that data supporting the findings of this study are available within the article.

Abbreviations

TIPS: transjugular intrahepatic portosystemic shunting; PVS: peritoneovenous shunting; POD: postoperative day

| References | ▴Top |

- Liu GF, Srinivasan A, Mutnuri S, Yerramadha MR, Agraharkar M. Acute abdomen from umbilical hernia rupture to flood syndrome: a case report and review of literature. J Med Cases. 2019;10(10):309-311.

doi pubmed - Malespin M, Moore CM, Fialho A, de Melo SW, Jr., Benyashvili T, Kothari AN, di Sabato D, et al. Case series of 10 patients with cirrhosis undergoing emergent repair of ruptured umbilical hernias: natural history and predictors of outcomes. Exp Clin Transplant. 2019;17(2):210-213.

doi pubmed - Telem DA, Schiano T, Divino CM. Complicated hernia presentation in patients with advanced cirrhosis and refractory ascites: management and outcome. Surgery. 2010;148(3):538-543.

doi pubmed - Blanco Teres L, Valdes de Anca A, Correa Bonito A, Gancedo Quintana A, Martin Perez E. Flood syndrome: a severe complication of umbilical hernia. Cir Esp (Engl Ed). 2020;98(8):490-491.

doi pubmed - Fasullo M. A rare case of flood syndrome and a perspective on management. The American Journal of Gastroenterology. 2017;112(Supplement 1):S1256.

doi - Gil AG, Rockwell B, Galen B. Flood syndrome, a rare complication of cirrhosis. The American Journal of Gastroenterology. 2019;114:S1309.

doi - DeLuca IJ, Grossman ME. Flood syndrome. JAAD Case Rep. 2015;1(1):5-6.

doi pubmed - Colbran R, Smith A, Melloy A, Iyer R. Spontaneous umbilical hernia rupture with omental evisceration and flood syndrome. International Surgery Journal. 2019;6(10):3830-3833.

doi - Nguyen ET, Tudtud-Hans LA. Flood syndrome: spontaneous umbilical hernia rupture leaking ascitic fluid-a case report. Perm J. 2017;21:16-152.

doi - Tan DWJ, Chan JJ. A rare case of flood syndrome in emergency department: A case report and review of recent reported cases. Hong Kong Journal of Emergency Medicine. 2020.

doi - Long WD, Hayden GE. Images in emergency medicine. Man with rushing fluid from his umbilicus. Flood syndrome. Ann Emerg Med. 2013;62(4):431.

doi pubmed - Drake C, Arowojolu O, Mitchell O, Liu S. Flood syndrome: not your average paracentesis. Journal of Hospital Medicine. 2017;12(Suppl 2):Abstract 427.

doi - Lemmer JH, Strodel WE, Knol JA, Eckhauser FE. Management of spontaneous umbilical hernia disruption in the cirrhotic patient. Ann Surg. 1983;198(1):30-34.

doi pubmed - Choo EK, McElroy S. Spontaneous bowel evisceration in a patient with alcoholic cirrhosis and an umbilical hernia. J Emerg Med. 2008;34(1):41-43.

doi pubmed - Sheikh MM, Siraj B, Fatima F, Ehsan H, Shahid MH. Flood Syndrome: A Rare and Fatal Complication of Umbilical Hernia in Liver Cirrhosis. Cureus. 2020;12(8):e9915.

doi - Oosterwijk PR, Kouw E, de Vos tot Nederveen Cappel WH. Two cases of spontaneous rupture of an umbilical hernia, a rare complication of portal hypertension. Archives of Clinical Gastroenterology 2017;3(3):071-073.

- Chatzizacharias NA, Bradley JA, Harper S, Butler A, Jah A, Huguet E, Praseedom RK, et al. Successful surgical management of ruptured umbilical hernias in cirrhotic patients. World J Gastroenterol. 2015;21(10):3109-3113.

doi pubmed - Azeem A, Latif S, Pervez A. A rare case of spontaneous umbilical hernia rupture- flood syndrome. The American Journal of Gastroenterology, 2016;(Suppl 1):S903-S904.

doi - Singh S, Skef W, Thaker S, Chan C. A case of flood syndrome: to operate or not to operate? American Journal of Gastroenterology. 2018;113:S1322.

doi - Kirkpatrick S, Schubert T. Umbilical hernia rupture in cirrhotics with ascites. Dig Dis Sci. 1988;33(6):762-765.

doi pubmed - Miryala R, Neilan R. Images in clinical medicine. Perforated umbilical hernia. N Engl J Med. 2009;360(25):e32.

doi pubmed - Fagan SP, Awad SS, Berger DH. Management of complicated umbilical hernias in patients with end-stage liver disease and refractory ascites. Surgery. 2004;135(6):679-682.

doi pubmed - O'Connor M, Allen JI, Schwartz ML. Peritoneovenous shunt therapy for leaking ascites in the cirrhotic patient. Ann Surg. 1984;200(1):66-69.

doi pubmed - Chikamori F, Mizobuchi K, Ueta K, Takasugi H, Yukishige S, Matsuoka H, Hokimoto N, et al. Flood syndrome managed by partial splenic embolization and percutaneous peritoneal drainage. Radiol Case Rep. 2021;16(1):108-112.

doi pubmed - Podymow T, Sabbagh C, Turnbull J. Spontaneous paracentesis through an umbilical hernia. CMAJ. 2003;168(6):741.

- Melcher ML, Lobato RL, Wren SM. A novel technique to treat ruptured umbilical hernias in patients with liver cirrhosis and severe ascites. J Laparoendosc Adv Surg Tech A. 2003;13(5):331-332.

doi pubmed - Sadik KW, Bonatti H, Schmitt T. Injection of fibrin glue for temporary treatment of an ascites leak from a ruptured umbilical hernia in a patient with liver cirrhosis. Surgery. 2008;143(4):574.

doi pubmed - European Association for the Study of the Liver. EASL clinical practice guidelines on the management of ascites, spontaneous bacterial peritonitis, and hepatorenal syndrome in cirrhosis. J Hepatol. 2010;53(3):397-417.

doi pubmed - Coelho JC, Claus CM, Campos AC, Costa MA, Blum C. Umbilical hernia in patients with liver cirrhosis: A surgical challenge. World J Gastrointest Surg. 2016;8(7):476-482.

doi pubmed

This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution Non-Commercial 4.0 International License, which permits unrestricted non-commercial use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited.

Gastroenterology Research is published by Elmer Press Inc.