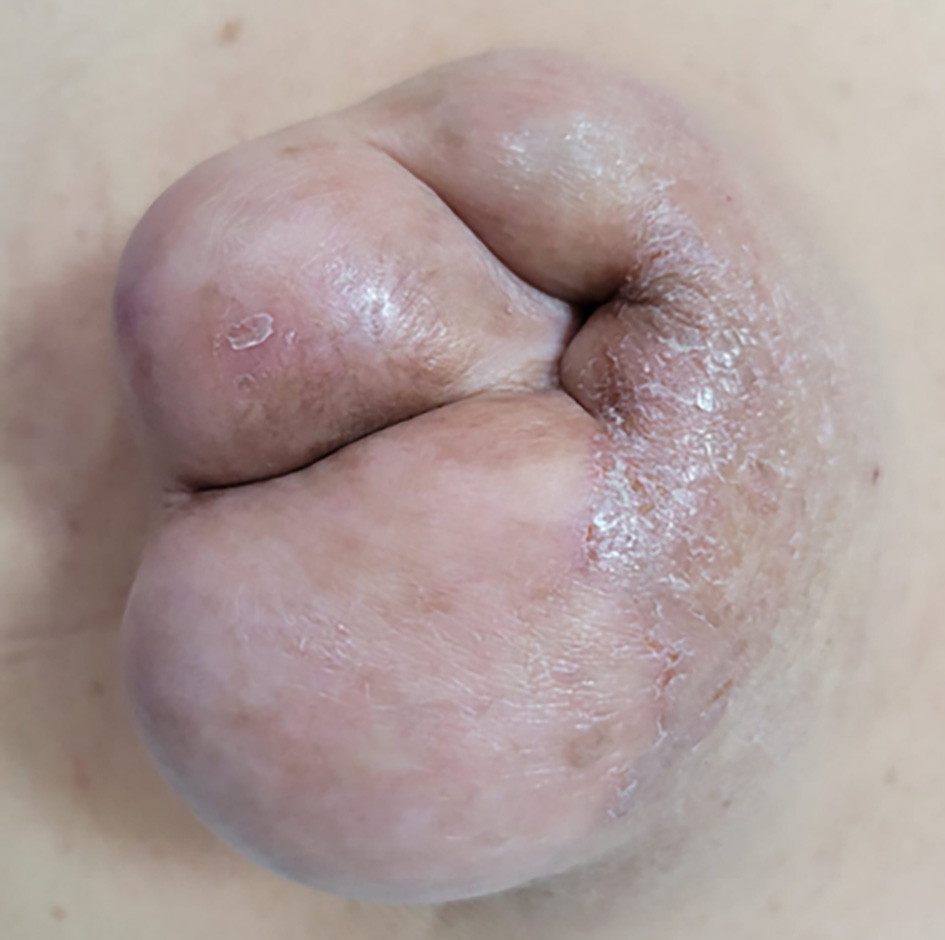

Figure 1. Ulcerated umbilical hernia.

| Gastroenterology Research, ISSN 1918-2805 print, 1918-2813 online, Open Access |

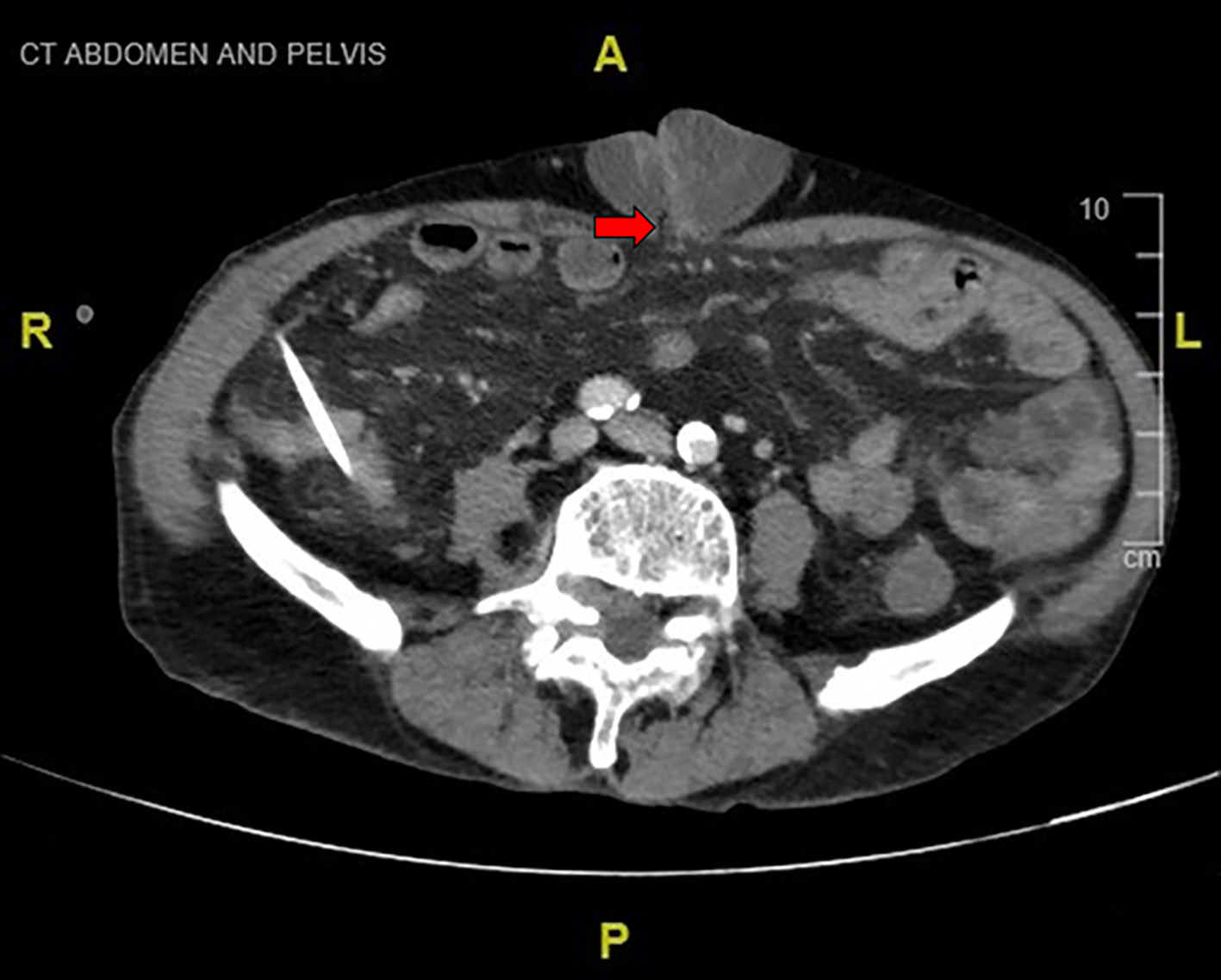

| Article copyright, the authors; Journal compilation copyright, Gastroenterol Res and Elmer Press Inc |

| Journal website https://www.gastrores.org |

Case Report

Volume 15, Number 4, August 2022, pages 217-224

Flood Syndrome

Figures

Table

| Technique | Description | Study design | Outcomes | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| POD: postoperative day; PVS: peritoneovenous shunting; TIPS: transjugular intrahepatic portosystemic shunting. | ||||

| Medical management | ||||

| Conservative | Salt restriction, diuretics, sterile dressings, antibiotics | Case report | Death: 2 months after from rupture of esophageal varices. | [25] |

| Ostomy pouch, diuretics and antibiotics | Case report | Survived with complications: recurrent admissions, spontaneous bacterial peritonitis, hyponatremia, and renal injury. | [1] | |

| Pressure dressings, diuretics and antibiotics | Case series: two cases, with one case managed conservatively | Survived with good outcome: underwent PVS due to refractory ascites, 2 years’ follow-up with no recurrence of ascitic leak. | [20] | |

| Fibrin glue | Five milliliters fibrin glue into the fascial defect and diuretics | Case report | Survived with good outcome: no recurrence in 12 months’ follow-up. | [26] |

| Five milliliters fibrin glue into the base of the ulcerated leaking of the hernia after ascitic drainage | Case report | Survived with good outcome: no recurrence in 4 months’ follow-up. | [27] | |

| Surgical management | ||||

| Percutaneous abdominal drain for secondary intention closure of the defect | Pigtail drain | Case report | Survived with good outcome. | [4] |

| Pigtail drain | Case report | Survived with complications: discharged with drain however defaulted follow-up and represented in 6 weeks with peritonitis. | [9] | |

| Partial splenic embolization and temporary percutaneous peritoneal drainage | 16 Fr. Drain inserted in the left lower abdominal quadrant. Partial splenic embolization using gelatin sponge and microcoils. | Case report | Survived with good outcome. | [24] |

| PVS | Closure of fascial defect and PVS, either simultaneous or sequential. | Case series: four patients had spontaneous umbilical hernia rupture. | Survived with good outcome: three patients at 3 - 19 months’ follow-up. Death: one patient died 2 years later from gastrointestinal bleed. | [23] |

| Peritoneovenous shunting under local anesthesia. | Case series: one patient underwent hernia repair. | Survived with good outcome: at 2 years’ follow-up. | [20] | |

| TIPS | TIPS without hernia repair. | Case report | Survived with complications: acute kidney injury and septic shock secondary to cholecystitis, subsequently recovered. | [7] |

| TIPS before surgical umbilical hernia repair. | Case report | Survived with good outcome. | [5] | |

| Retrospective chart review: four patients had TIPS before hernia repair. | Survived with good outcome: two patients. Survived with complications: one patient had worsening encephalopathy; one underwent liver transplant for liver decompensation. | [3] | ||

| Case series | Survived with good outcome: no recurrence at 5 - 13 months’ follow-up. | [22] | ||

| Case series: two patients | Survived with good outcome. | [2] | ||

| Retrospective chart review: four patients. | Survived with good outcome: two patients. Survived with complications: one patient had worsening encephalopathy requiring supportive care; one patient had liver decompensation requiring liver transplant. | [3] | ||

| Umbilical hernia repair/closure | Primary repair without mesh, excision of excessive necrotic skin. | Case series: eight patients | Death: one patient. Survived with complications: two patients had liver decompensation requiring liver transplant. Survived with good outcome: five patients. | [2] |

| In all cases, with one exception, a primary repair with non-absorbable Nylon, interrupted sutures, without mesh. | Case series | Survived with complications: nine patients (wound infection, antibiotics allergy, ileus, and liver transplant). Survived with good outcome: one patient at 54 months’ follow-up. | [17] | |

| One patient had elective repair with onlay polypropylene mesh. | Survived with good outcome at 9 months’ follow-up. | |||

| Primary open surgical repair of umbilical hernia with JP drain placement. | Case report | Survived with good outcome at 8 months’ follow-up. | [18] | |

| Umbilical herniorrhaphy without mesh and drain insertion. | Case report | Survived with complications: acute kidney injury, spontaneous pneumothorax, failure to thrive - discharged to hospice care. | [15] | |

| Closure of umbilical defect. | Case report | Survived with good outcome: discharged 2 days later with oral antibiotics. | [11] | |

| Emergent repair no drain insertion. | Retrospective chart review: two patients | Survived with complications: one patient had ascitic leak underwent TIPS on POD 5, one had liver decompensation requiring liver transplant. | [3] | |

| Debridement of necrotic skin overlying the hernia, running closure of the fascia with continuous non-absorbable suture (2-0 polypropylene), and primary closure of the skin. | Case series | Death: one patient (colonic dilatation and liver failure). Survived with complications: one patient (wound infection which healed). Survived with good outcome: seven patients. | [13] | |

| Resection of infarcted omentum and primary closure of hernia defect with interrupted 1-0 nylon sutures. | Case report | Survived with complications: aspiration pneumonia, decompensated liver disease, feed intolerance, spontaneous bacterial peritonitis - discharged after 32 days of hospitalization with no hernia recurrence. | [8] | |

| Excision of ulcerated umbilical skin, hernial sac and ring, and primary closure of incision. | Case report | Survived with complications: alcohol withdrawal syndrome, discharged on day 7 of admission. | [14] | |

| Excision of necrotic skin and hernia sac, closure of umbilical defect with polydioxanone sutures, insertion of abdominal drain. | Case series | Survived with complications: recurrent hernia defect with incarcerated bowel; underwent resection of strangulated omentum and closure of hernia defect with onlay monofilament polypropylene mesh, prosthetic mesh infection and bacterial peritonitis; readmission 1 year later with refractory ascites and encephalopathy. | [16] | |

| Excision of hernia sac and closure of peritoneum with polydioxanone sutures and hernial defect with 6 × 6 cm soft polypropylene sublay mesh. | Survived with good outcome. | |||

| Primary closure with drain insertion. | Case report | Survived with good outcome. | [12] | |

| Biomesh hernia repair. | Case report | Survived with good outcome. | [19] | |

| Bedside closure of umbilical hernia ulcer and ascitic drain insertion. | Case report | Survived with complications: bacterial peritonitis treated with antibiotics - improvement in condition and discharged after 6 days. | [10] | |

| Closure of skin over umbilical hernia under local anesthesia with simple running nonabsorbable monofilament suture, defect in the skin overlying the recurrent umbilical hernia was oversewn. | Case series: one case underwent PVS. | Death: readmitted with umbilical hernia rupture 2 months later with acute renal failure and death. | [20] | |

| Exploratory laparotomy and umbilical wall defect repair. | Case report | Not mentioned. | [6] | |

| Resection of strangulated omentum and repair of abdominal wall defect. | Case report | Not mentioned. | [21] | |