| Gastroenterology Research, ISSN 1918-2805 print, 1918-2813 online, Open Access |

| Article copyright, the authors; Journal compilation copyright, Gastroenterol Res and Elmer Press Inc |

| Journal website http://www.gastrores.org |

Case Report

Volume 10, Number 6, December 2017, pages 372-375

Esophageal Granular Cell Tumor: A Case and Review of the Literature

Emmanuel Oforia, Daryl Ramaia, b, d, Ying X. Luic, Madhavi Reddya

aDepartment of Gastroenterology and Hepatology, The Brooklyn Hospital Center, Academic Affiliate of The Icahn School of Medicine at Mount Sinai, Clinical Affiliate of The Mount Sinai Hospital, 121 DeKalb Avenue, Brooklyn, NY 11201, USA

bDepartment of Anatomical Sciences, St. George’s University School of Medicine, True Blue, Grenada, WI

cDepartment of Pathology, The Brooklyn Hospital Center, Academic Affiliate of The Icahn School of Medicine at Mount Sinai, Clinical Affiliate of The Mount Sinai Hospital, 121 DeKalb Avenue, Brooklyn, NY 11201, USA

dCorresponding Author: Daryl Ramai, Department of Anatomical Sciences, St. George’s University School of Medicine, Grenada, WI

Manuscript submitted August 21, 2017, accepted September 28, 2017

Short title: Granular Cell Tumor of the Esophagus

doi: https://doi.org/10.14740/gr898w

| Abstract | ▴Top |

Granular cell tumors (GCTs) are rare and benign tumors that can occur at any anatomical site. GCTs are thought to originate from nerve cells, particularly Schwann cells. Their name derives from the fact that an accumulation of cytoplasmic lysosomes imparts the tumor with a granular appearance. They are most commonly observed in the oral cavity, skin and subcutaneous tissue, breast, and respiratory tract. GCTs rarely affect the gastrointestinal tract. We report a 56-year-old female with a medical history of human immunodeficiency virus, hepatitis C, and cholelithiasis, who presented with abdominal pain. Upper endoscopy revealed a 1 - 2 cm solitary yellowish appearing nodule just distal to the GE junction. Biopsy of the nodule followed by histopathology was positive for S100, but negative for pancytokeratin immunostains. PAS staining highlighted cytoplasmic granules, further supporting the diagnosis of gastrointestinal GCT.

Keywords: Granular cell tumor; Esophagus; Gastrointestinal tract; S100

| Introduction | ▴Top |

Granular cell tumors (GCTs) are rare and benign neoplasms originating in Schwann cells of the nervous system. Though GCTs were first reported in 1926 by Abrikossoff, and initially described as Abrikossoff’s tumors or granular cell myoblastomas, esophageal GCTs were first reported in 1931 [1, 2]. While it is unclear of the prevalence of esophageal GCTs, one study reported that these tumors account for less than 1% of all benign esophageal tumors [3]. Most cases are fortuitously identified upon upper endoscopic examination for other indications. We report a case of esophageal GCT in a patient with Helicobacter pylori gastritis, and review the literature on the clinical presentation, diagnosis, endoscopic and ultrasound features, and management of esophageal GCTs.

| Case Report | ▴Top |

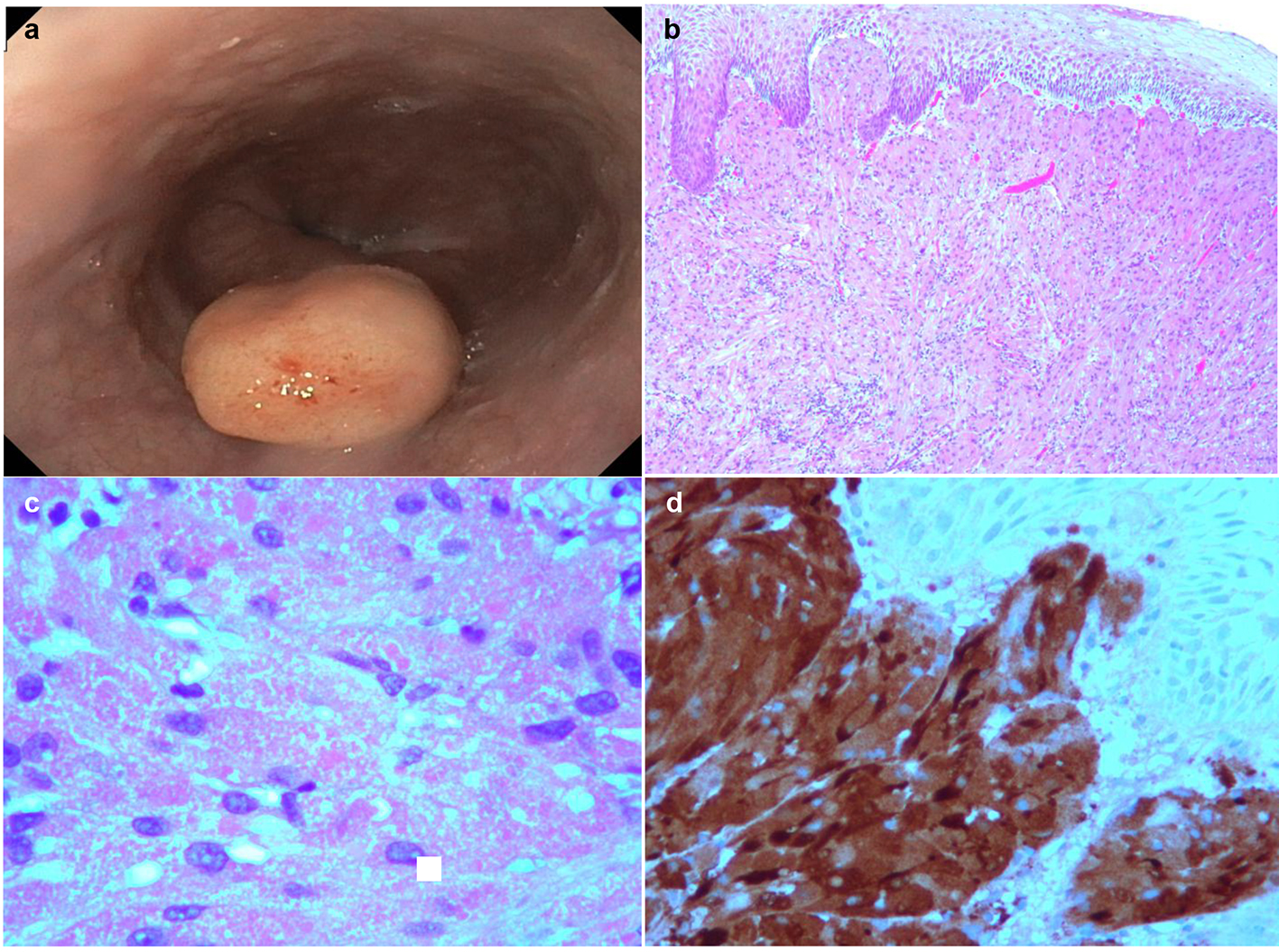

A 56-year-old female with a medical history of human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) diagnosed in 1986 (on HAART), hepatitis C (completed 12 weeks treatment), and cholelithiasis, presented with abdominal pain and non-specific dyspeptic symptoms. Vital signs showed HR 72 bpm, temperature 98.3 °F, RR 14 bpm, and BP 134/73 mm Hg. Her physical exam was unremarkable, and she denied alcohol consumption and smoking or drugs. Laboratory findings showed Hgb 11.9 g/dL, hematocrit 38%, WBC 4.6 × 103/µL, and platelet 136 × 103/µL. HIV viral load was undetectable, CD4 count was 742 cells/µL, and sedimentation rate was 25. Upper endoscopy was performed which showed a 1 cm yellowish appearing esophageal nodule just distal to the GE junction. Mildly erythematous mucosa was found in the antrum and body of the stomach, suggestive of mild non-erosive gastritis. Multiple biopsies were taken from the surrounding gastric mucosa and esophageal nodule. Histopathology of stomach biopsies showed the presence of H. pylori. The esophageal nodule was positive for S100, but negative for pancytokeratin immunostains. Additionally, PAS staining highlighted cytoplasmic granules, consistent with the diagnosis of gastrointestinal GCT (Fig. 1).

Click for large image | Figure 1. (a) Solitary polyp measuring 1 - 2 cm covered by normal-appearing mucosa was found in the esophagus distal to the GE junction. (b) Micrographic examination (× 40) shows squamous cell epithelium and tumor cells. (c) High power micrographic examination (× 100) shows granular cytoplasm containing cells. (d) S100 positivity in GCT. |

| Discussion | ▴Top |

GCTs are rare clinical entities that are accidentally discovered during upper endoscopy for other indications. GCTs have a predilection towards females. Though these tumors can present at any age, they mainly occur in the 40 - 49 years old cohort [4]. Most GCTs are typically solitary and benign, and are most commonly located in the middle to distal esophagus [5]. Orlowska et al (1993) reported that two-thirds of esophageal GCTs were located in the distal esophagus, while 20% and 15% occurred in middle and proximal regions, respectively [6]. Similarly, Wang and Liu (2015) reported that 80% of cases of esophageal GCTs were found in the distal or middle esophagus, while 20% occurred in the upper region [7]. Goldblum et al (1996) reported that 92% of esophageal GCTs were located in the distal esophagus [4].

The clinical presentation of GCTs is vague and non-specific. In fact, most GCTs are asymptomatic and commonly present as a non-specific painless mass. Clinical symptoms related to GCTs are dependent on the size of the tumor, where small tumors (< 1 cm) are asymptomatic, and larger tumors (> 1 cm) may experience dysphagia [8]. A study of nine patients diagnosed with esophageal GCT reported initial complaints of abdominal distension, acid reflux, bloating, and loss of appetite [5]. Another case series reported symptoms of intermittent heartburn, dysphagia, acid reflux with intermittent abdominal distension and belching, and sternal chest pain [7]. Zhang et al (2014) reported that dysphagia was more likely in patients whose tumor was greater than 1.5 cm [9]. Interestingly, a majority of cases are not diagnosed due to dysphagia.

Most esophageal GCTs are found incidentally upon upper endoscopic screening for other indications. Endoscopically, GCTs appear as sessile, white-to-grey, pink, or yellow lesions [10]. These tumors are usually raised with a smooth surface, and typically involve the submucosa. GCTs can involve the mucosa and muscularis propria, similar to leiomyomas. In rare cases, larger tumors may present with ulceration and necrosis [11]. Endoscopic ultrasound (EUS) is diagnostically utilized for ascertaining the degree of tumor invasion, and can also provide tissue sampling through the use of fine needle aspiration (FNA). Palazzo et al (1997) reported using EUS, GCTs appear as round, hypoechoic and homogeneous lesions, with clear borders [12]. However, other cases have reported GCTs as heterogeneous lesions with irregular margins on EUS, often mistaken for lipomas [11, 13].

While EUS and endoscopy aids in narrowing the differential diagnosis, the diagnosis of GCT is confirmed upon histopathological examination. Key histological features of GCTs include nests of polygonal cells with small, round nuclei that are rich in granular cytoplasm. The overlying mucosal is often accompanied with pseudoepitheliomatous hyperplasia. More often than not, GCTs can mimic or co-exist with esophageal squamous cell cancer, specifically spindle-cell squamous cancers [14, 15]. Immunohistochemical staining differentiates and provides confirmation of GCTs. Positive staining of S100 was first reported in 1986, since then, other positive markers have been reported including neuron-specific enolase and nestin [2, 6, 16, 17]. Negative markers include CD117, CD34, desmin, cytokeratin, SMA, glial fibrillary acidic protein, inhibin-α, myoglobin, fibronectin and carcinoembryonic antigen [9, 16, 18, 19].

While esophageal GCTs are regarded as benign tumors, approximately 1-3% of cases have reported malignant degeneration with a 5-year survival rate < 35% [20]. Histologically, malignant GCTs display features such as necrosis, spindling, vesicular nuclei with large nucleoli, increased mitotic activity, high nuclear to cytoplasmic ratio, and pleomorphism. Fanburg-Smith et al (1998) reported that malignant GCT is a high-grade sarcoma with a high rate of metastases and a short survival. In their study, 46 of 72 cases were defined as histologically malignant. Of 28 cases with follow-up information, 14 (50%) revealed metastasis, nine (32%) showed recurrence, and 11 (32%) died of disease at a median interval of 3 years [21].

GCTs can be managed conservatively, endoscopically, or surgically. Patients with tumors less than 1 cm in diameter are treated conservatively. These patients are followed up with periodic endoscopies providing that biopsy shows no signs of malignancy. In cases where the tumor is greater than 1 cm, lesions are removed by endoscopic mucosal resection (EMR) or endoscopic submucosal dissection (ESD). EMR, though widely used, has limitations which should be kept in mind. Larger tumors have a propensity to invade surrounding structures or deeper layers such as the muscularis propria. This poses a therapeutic challenge in the ability to completely excise the growing tumor. Zhong et al (2011) reported that EMR was not completely successful in the removal of an esophageal GCT greater than 1.3 cm [11]. ESD has emerged as a promising technique which circumferentially removes the tumor along with the submucosal layer. This method allows complete removal of the tumor as a whole [22]. Though ESD is more effective, there is greater risk of bleeding and perforation compared to EMR. In cases of malignancy where tumor invasion is more aggressive, surgery should be considered. In these cases, patients should be followed up with endoscopic surveillance postoperatively.

Conclusion

GCTs are rare and benign tumors of the esophagus. In the clinical context, esophageal GCTs should be considered as a differential diagnosis in middle age patients who present with symptoms of dysphagia or dyspepsia. Most esophageal GCTs are located in the distal esophagus. In evaluating disease extent, EUS aids in ascertaining tumor invasion and treatment options. Treatment is based upon the size of the tumor, evidence of malignant degeneration, and clinical judgement regarding the use of EMR, ESD, or surgery.

| References | ▴Top |

- Abrikossoff A. Myomas originating from transversely striated voluntary musculature. Virchows Arch A Pathol Anat Histol. 1926;260:215-233.

doi - Abrikossoff A. Further investigations on myoblastomas. Virchows Arch Pathol Anat Physiol Klin Med. 1931;280:723-740.

doi - Terada T. Benign Tumors of the Esophagus: A Histopathologic Study of 49 Cases among 931 Consecutive Esophageal Biopsies. Gastroenterology Res. 2009;2(2):100-103.

doi - Goldblum JR, Rice TW, Zuccaro G, Richter JE. Granular cell tumors of the esophagus: a clinical and pathologic study of 13 cases. Ann Thorac Surg. 1996;62(3):860-865.

doi - Xu GQ, Chen HT, Xu CF, Teng XD. Esophageal granular cell tumors: report of 9 cases and a literature review. World J Gastroenterol. 2012;18(47):7118-7121.

doi pubmed - Orlowska J, Pachlewski J, Gugulski A, Butruk E. A conservative approach to granular cell tumors of the esophagus: four case reports and literature review. Am J Gastroenterol. 1993;88(2):311-315.

pubmed - Wang HQ, Liu AJ. Esophageal granular cell tumors: Case report and literature review. World J Gastrointest Oncol. 2015;7(8):123-127.

doi pubmed - Voskuil JH, van Dijk MM, Wagenaar SS, van Vliet AC, Timmer R, van Hees PA. Occurrence of esophageal granular cell tumors in The Netherlands between 1988 and 1994. Dig Dis Sci. 2001;46(8):1610-1614.

doi pubmed - Zhang M, Sun ZQ, Zou XP. Esophageal granular cell tumor: Clinical, endoscopic and histological features of 19 cases. Oncol Lett. 2014;8(2):551-555.

doi - De Rezende L, Lucendo AJ, Alvarez-Arguelles H. Granular cell tumors of the esophagus: report of five cases and review of diagnostic and therapeutic techniques. Dis Esophagus. 2007;20(5):436-443.

doi pubmed - Zhong N, Katzka DA, Smyrk TC, Wang KK, Topazian M. Endoscopic diagnosis and resection of esophageal granular cell tumors. Dis Esophagus. 2011;24(8):538-543.

doi pubmed - Palazzo L, Landi B, Cellier C, Roseau G, Chaussade S, Couturier D, Barbier J. Endosonographic features of esophageal granular cell tumors. Endoscopy. 1997;29(9):850-853.

doi pubmed - Buscarini E, Stasi MD, Rossi S, Silva M, Giangregorio F, Adriano Z, Buscarini L. Endosonographic diagnosis of submucosal upper gastrointestinal tract lesions and large fold gastropathies by catheter ultrasound probe. Gastrointest Endosc. 1999;49(2):184-191.

doi - Lack EE, Worsham GF, Callihan MD, Crawford BE, Klappenbach S, Rowden G, Chun B. Granular cell tumor: a clinicopathologic study of 110 patients. J Surg Oncol. 1980;13(4):301-316.

doi pubmed - Szumilo J, Dabrowski A, Skomra D, Chibowski D. Coexistence of esophageal granular cell tumor and squamous cell carcinoma: a case report. Dis Esophagus. 2002;15(1):88-92.

doi pubmed - Parfitt JR, McLean CA, Joseph MG, Streutker CJ, Al-Haddad S, Driman DK. Granular cell tumours of the gastrointestinal tract: expression of nestin and clinicopathological evaluation of 11 patients. Histopathology. 2006;48(4):424-430.

doi pubmed - Miwa K, Hattori T, Hosokawa Y, Nakamura Y, Isobe Y, Fujisawa K, Nakagawara G. Granular cell tumor of the esophagus. Gastroenterol Jpn. 1986;21(5):508-512.

pubmed - Maekawa H, Maekawa T, Yabuki K, Sato K, Tamazaki Y, Kudo K, Wada R, et al. Multiple esophagogastric granular cell tumors. J Gastroenterol. 2003;38(8):776-780.

doi pubmed - Mitomi H, Matsumoto Y, Mori A, Arai N, Ishii K, Tanabe S, Kobayashi K, et al. Multifocal granular cell tumors of the gastrointestinal tract: Immunohistochemical findings compared with those of solitary tumors. Pathol Int. 2004;54(1):47-51.

doi pubmed - David O, Jakate S. Multifocal granular cell tumor of the esophagus and proximal stomach with infiltrative pattern: a case report and review of the literature. Arch Pathol Lab Med. 1999;123(10):967-973.

pubmed - Fanburg-Smith JC, Meis-Kindblom JM, Fante R, Kindblom LG. Malignant granular cell tumor of soft tissue: diagnostic criteria and clinicopathologic correlation. Am J Surg Pathol. 1998;22(7):779-794.

doi pubmed - Zhou PH, Yao LQ, Qin XY, Xu MD, Zhong YS, Chen WF, Ma LL, et al. Advantages of endoscopic submucosal dissection with needle-knife over endoscopic mucosal resection for small rectal carcinoid tumors: a retrospective study. Surg Endosc. 2010;24(10):2607-2612.

doi pubmed

This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution Non-Commercial 4.0 International License, which permits unrestricted non-commercial use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited.

Gastroenterology Research is published by Elmer Press Inc.