| Gastroenterology Research, ISSN 1918-2805 print, 1918-2813 online, Open Access |

| Article copyright, the authors; Journal compilation copyright, Gastroenterol Res and Elmer Press Inc |

| Journal website http://www.gastrores.org |

Case Report

Volume 12, Number 1, February 2019, pages 48-51

Malignant Peritoneal Mesothelioma Without Asbestos Exposure

Hafsa Abbasa, Julio C Rodrigueza, Hassan Tariqb, Masooma Niazic, Ahmed Alemama, d, Suresh Kumar Nayudub

aDepartment of Medicine, Bronxcare Health System, Bronx, NY 10457, USA

bDepartment of Gastroenterology, Bronxcare Health System, Bronx, NY 10457, USA

cDepartment of Pathology, Bronxcare Health System, Bronx, NY 10457, USA

dCorresponding Author: Ahmed Alemam, Bronxcare Health System, 1650 Grand Concourse, Bronx, NY 10457, USA

Manuscript submitted January 23, 2019, accepted February 4, 2019

Short title: MPM Without Asbestos Exposure

doi: https://doi.org/10.14740/gr1141

| Abstract | ▴Top |

Malignant mesothelioma is a rare neoplasm of the serosal linings. Mesothelioma has been linked to asbestos exposure, with prior asbestos exposure linked to 33-50% of malignant peritoneal mesotheliomas. We describe a case of malignant peritoneal mesothelioma (MPM) without any prior exposure to asbestos in a 40-year-old Hispanic female who presented to the emergency department with worsening abdominal pain and distension. She had a history of beta thalassemia trait and iron deficiency anemia. Examination revealed a distended abdomen with protruding umbilicus and positive shifting dullness. Laboratory tests showed anemia. Computed tomography (CT) of the abdomen revealed massive complex ascites suspicious of a malignant process. Ascitic fluid analysis showed serum ascites albumin gradient (SAAG) of 1.1 g/dL with a total protein of 5.2 g/dL. She underwent laparoscopic peritoneal biopsy which yielded epithelioid type malignant mesothelioma. She was started on chemotherapy with cisplatin and pemetrexed. The last follow-up was 27 months after the diagnosis. MPM is a rare and life-threatening malignancy. Frequently, the symptoms are non-specific. This poses a diagnostic challenge for physicians and probably the reason why the diagnosis is often delayed, especially in the absence of risk factors.

Keywords: Malignant peritoneal mesothelioma; Asbestos; Risk factors

| Introduction | ▴Top |

Malignant mesothelioma is a rare neoplasm of the serosal linings involving the pleura, peritoneum, pericardium, and tunica vaginalis of testes. Mesothelioma has been linked to asbestos exposure, but an association with silica and radiation has also been reported. Visceral pleura is the most common site, followed by peritoneum [1]. Peritoneal mesothelioma was first reported in 1908 by Miller and Wynn. Malignant mesothelioma of the peritoneum constitutes 7-30% of all mesotheliomas [2-5]. The highest rates of mesotheliomas have been reported in industrialized countries. Asbestos exposure has been evident in 80% of cases of pleural mesothelioma, while 33-50% of malignant peritoneal mesotheliomas (MPMs) are linked to prior asbestos exposure [6-8]. MPM can occur at any age but usually presents in the fifth and sixth decades of life [9, 10]. It is more common in men, generally attributed to higher rates of occupational, industrial toxin exposure [11]. Patients typically present with abdominal pain, distention of abdomen, anorexia, weight loss and ascites [12]. The less frequent presentations include a fever of unknown origin, hypercoagulability and intestinal obstruction [12, 13]. A nonspecific clinical presentation may pose a diagnostic challenge for the physicians especially in the absence of risk factors. We describe a case of MPM without any prior exposure to asbestos or other risk factors.

| Case Report | ▴Top |

We report a case of a 40-year-old Hispanic female who was evaluated in the emergency room (ER) for worsening abdominal pain and distension. She had been in her usual state of health until 2 months before this admission. She was initially evaluated by her primary care physician (PCP) for abdominal distension. The initial workup form PCP office showed mild anemia, hepatomegaly secondary to fatty infiltration and ascites on ultrasound of abdomen. She was referred to the outpatient gastroenterology clinic by PCP; however patient presented to ER due to worsening abdominal pain.

On admission to this hospital, she reported that her abdominal pain and distension have been worsening for the past 3 weeks. She described the pain to be sharp, diffuse, non-radiating, rated 10 on a scale of 0 to 10, with 10 indicating the most severe pain. There was no nausea, vomiting, diarrhea, constipation, weight loss or change in appetite. She had regular bowel movements but had noticed several episodes of blood while wiping herself a few weeks ago. Two weeks before this presentation she had dysuria, which had resolved spontaneously in 1 day. However, she did not have flank pain, foul-smelling urine, vaginal discharge or fever during that episode. She had not traveled outside the United States (US) recently and had not contacted any sick person. Her menstrual periods occurred in regular 30-day cycles, and her last menstrual period was 1 week before this presentation.

She had a history of beta thalassemia trait, iron deficiency anemia. She underwent tubal ligation 13 years ago. She had no known drug allergies. She was an active smoker with a 10-pack-year history of smoking. She consumed alcohol socially and reported using marijuana on a regular basis. Her active medications include omeprazole, acetaminophen, naproxen (as needed), and iron supplements. She was born and raised in the US. She lived with her husband and was sexually active. Her father had hypertension, and her aunt had breast cancer.

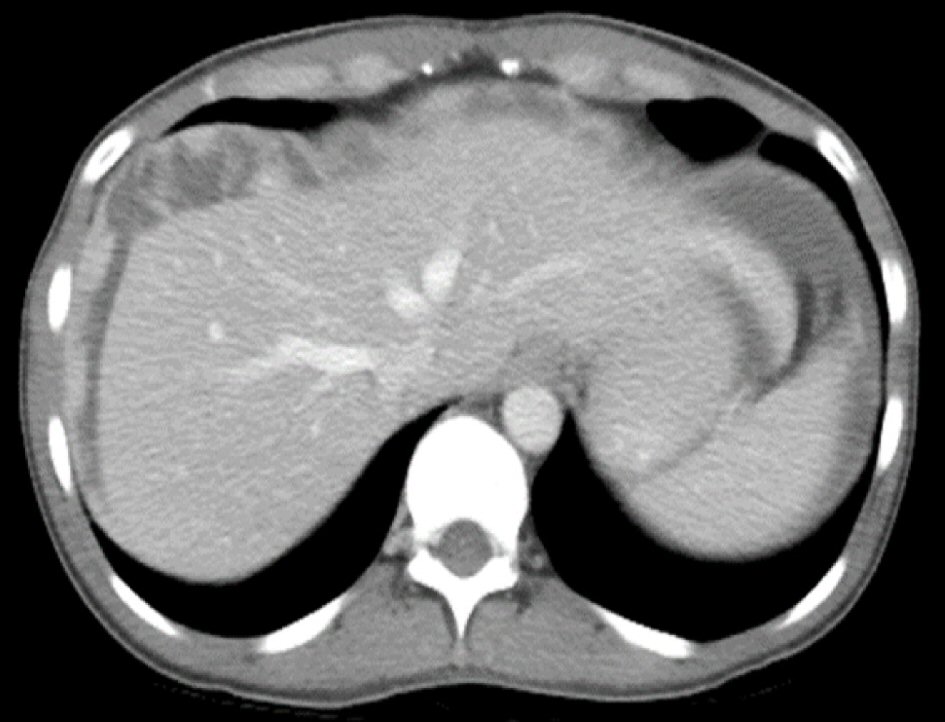

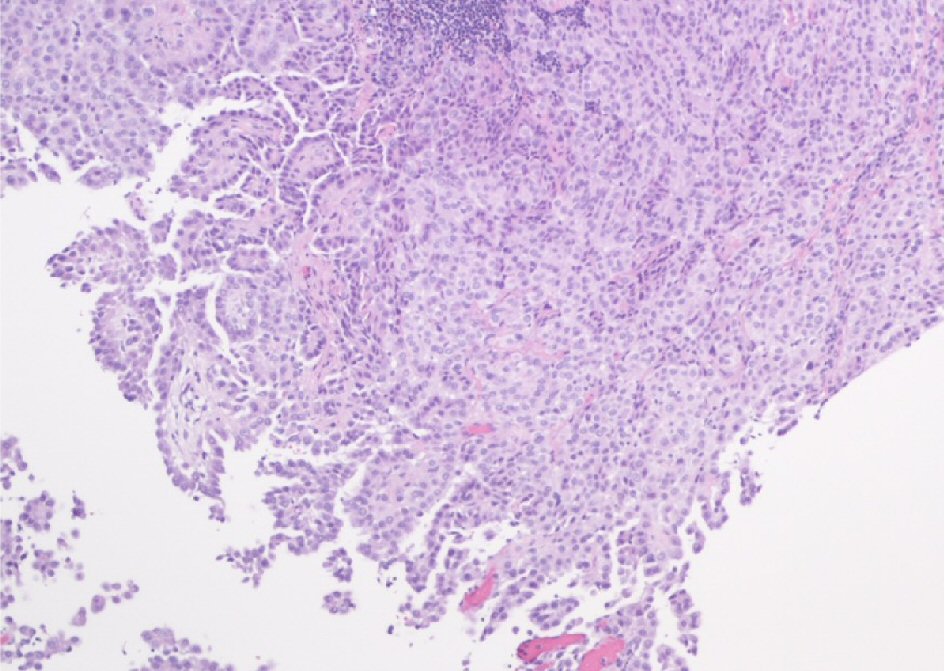

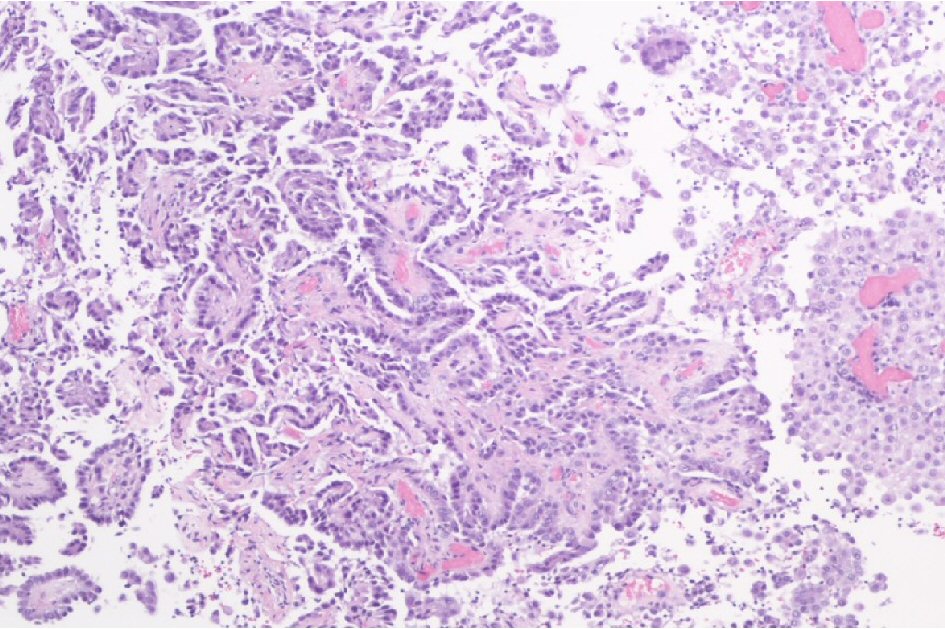

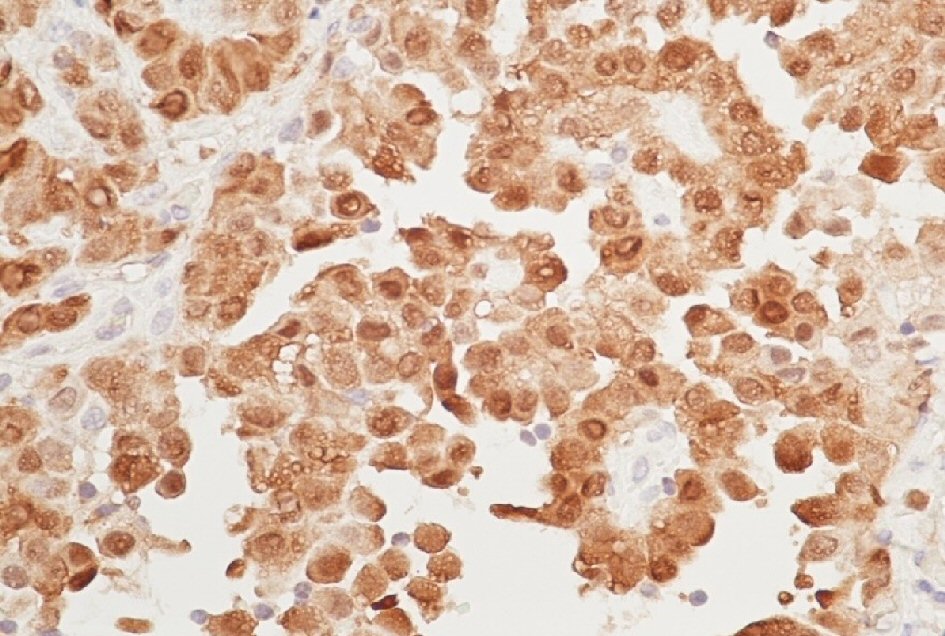

On initial evaluation, the temperature was 36.9 °C; the heart rate was 83 beats per minute, the blood pressure 111/59 mm Hg, the respiratory rate was 14 breaths per minute, and she was saturating 100% on room air. She was in mild distress due to pain and distension of abdomen. She was well developed and appeared in regular nutritional status. Abdominal examination revealed a distended abdomen with protruding umbilicus and positive shifting dullness suggestive of intra-abdominal fluid. Laboratory tests showed anemia, with hemoglobin of 11.3 g/dL. Her liver and renal function tests were within reasonable limits. Alpha1 anti-trypsin was marginally elevated (207 mg/dL). She was tested negative for viral hepatitis markers (Table 1). An echocardiogram was performed which did not show any signs of heart failure. Computed tomography (CT) of the abdomen with intravenous contrast revealed massive complex ascites with irregular nodular enhancement of the peritoneal wall (omental caking) suspicious of a malignant process (Fig. 1). She subsequently underwent CT-guided peritoneal tap which yielded 300 mL of serosanguinous fluid. Biochemical evaluation of the fluid showed serum ascites albumin gradient (SAAG) of 1.1 g/dL with a total protein of 5.2 g/dL pointing towards a differential diagnosis of carcinomatosis and tuberculosis (Table 2). Cytological examination of the fluid did not reveal any malignant cells. Considering lower yield of fluid cytology, patient was evaluated by the surgical team and underwent laparoscopic peritoneal biopsy which yielded epithelioid type malignant mesothelioma (Figs. 2-4). The patient was referred to a tertiary care oncology center for further management, where chemotherapy with cisplatin and pemetrexed was initiated. The patient has been healthy on the follow-up visits and continues to follow there for continued care.

Click to view | Table 1. Laboratory Test Results |

Click for large image | Figure 1. CT scan of the abdomen showing complex ascites and omental caking. |

Click to view | Table 2. Ascitic Fluid Analysis |

Click for large image | Figure 2. Diffuse malignant mesothelioma of epithelial type comprised of tubulopapillary pattern with papillary structures and branching tubules (H&E, magnification × 100). |

Click for large image | Figure 3. Diffuse malignant mesothelioma of epithelial type with predominantly papillary configuration lined by rather cuboidal to flattened epithelial-like cells with vesicular nuclei (H&E, magnification × 100). |

Click for large image | Figure 4. Calretinin immunostain shows strong positivity of tumor cells for the mesothelial cells (immunostain, magnification × 400). |

| Discussion | ▴Top |

Malignant peritoneal mesothelioma (MPM) is a rare and life-threatening malignancy. Several industrial chemicals and minerals like asbestos (most commonly), thorium and mica (more so in the development of pleural as compared to peritoneal mesothelioma) have been linked to the development of mesothelioma [1]. There is a wide variety of presentations of the disease including abdominal pain and abdominal distension being the most common. At many times the symptoms are vague and non-specific. This poses a diagnostic challenge for physicians and probably the reason why the diagnosis is often delayed, especially in the absence of risk factors [1].

There is no imaging that is specific and diagnostic, but CT abdomen with intravenous contrast is the modality of choice [14]. It can be seen as a solid, heterogeneous, soft tissue mass with irregular margins that is enhanced by contrast. Patients usually present at an advanced stage and are detected on imaging as a solid infiltrating mass or multiple small nodules involving the serosa. Ascites is seen in a vast majority of newly diagnosed patients [15, 16], while caking and thickening of the omentum, mesenteric nodules, and scalloping of intra-abdominal organs are noted on CT in some cases [17, 18]. A definitive diagnosis is only possible with a histologic and immunohistochemical examination of the tissue [6]. CT aids in staging and biopsy while a cytological analysis of the ascitic fluid has a low diagnostic yield [6]. Laparoscopy with tissue sampling will have the high yield in those cases. Some studies demonstrate the usefulness of diffusion-weighted and gadolinium-enhanced magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) in determining the tumor burden [19]. The standard of treatment is cytoreduction surgery with hyperthermic intraperitoneal chemotherapy. It has a poor 5-year survival rate of 50% and therefore requires an astute clinical acumen and a high degree of suspicion.

| References | ▴Top |

- Kim J, Bhagwandin S, Labow DM. Malignant peritoneal mesothelioma: a review. Ann Transl Med. 2017;5(11):236.

doi pubmed - Price B. Analysis of current trends in United States mesothelioma incidence. Am J Epidemiol. 1997;145(3):211-218.

doi pubmed - Price B, Ware A. Time trend of mesothelioma incidence in the United States and projection of future cases: an update based on SEER data for 1973 through 2005. Crit Rev Toxicol. 2009;39(7):576-588.

doi pubmed - Moolgavkar SH, Meza R, Turim J. Pleural and peritoneal mesotheliomas in SEER: age effects and temporal trends, 1973-2005. Cancer Causes Control. 2009;20(6):935-944.

doi pubmed - Henley SJ, Larson TC, Wu M, Antao VC, Lewis M, Pinheiro GA, Eheman C. Mesothelioma incidence in 50 states and the District of Columbia, United States, 2003-2008. Int J Occup Environ Health. 2013;19(1):1-10.

doi pubmed - Bridda A, Padoan I, Mencarelli R, Frego M. Peritoneal mesothelioma: a review. MedGenMed. 2007;9(2):32.

pubmed - Teta MJ, Mink PJ, Lau E, Sceurman BK, Foster ED. US mesothelioma patterns 1973-2002: indicators of change and insights into background rates. Eur J Cancer Prev. 2008;17(6):525-534.

doi pubmed - Boffetta P. Epidemiology of peritoneal mesothelioma: a review. Ann Oncol. 2007;18(6):985-990.

doi pubmed - Tandar A, Abraham G, Gurka J, Wendel M, Stolbach L. Recurrent peritoneal mesothelioma with long-delayed recurrence. J Clin Gastroenterol. 2001;33(3):247-250.

doi pubmed - Van de Walle P, Blomme Y, Van Outryve L. Laparoscopy and primary diffuse malignant peritoneal mesothelioma: a diagnostic challenge. Acta Chir Belg. 2004;104(1):114-117.

doi pubmed - Metintas S, Metintas M, Ucgun I, Oner U. Malignant mesothelioma due to environmental exposure to asbestos: follow-up of a Turkish cohort living in a rural area. Chest. 2002;122(6):2224-2229.

doi pubmed - de Pangher Manzini V. Malignant peritoneal mesothelioma. Tumori. 2005;91(1):1-5.

pubmed - Tejido Garcia R, Anta Fernandez M, Hernandez Hernandez JL, Bravo Gonzalez J, Gonzalez Macias J. [Fever of unknown origin as the clinical presentation of malignant peritoneal mesothelioma]. An Med Interna. 1997;14(11):573-575.

- Busch JM, Kruskal JB, Wu B, Armed Forces Institute of P. Best cases from the AFIP. Malignant peritoneal mesothelioma. Radiographics. 2002;22(6):1511-1515.

doi pubmed - Kebapci M, Vardareli E, Adapinar B, Acikalin M. CT findings and serum ca 125 levels in malignant peritoneal mesothelioma: report of 11 new cases and review of the literature. Eur Radiol. 2003;13(12):2620-2626.

doi pubmed - Ros PR, Yuschok TJ, Buck JL, Shekitka KM, Kaude JV. Peritoneal mesothelioma. Radiologic appearances correlated with histology. Acta Radiol. 1991;32(5):355-358.

doi pubmed - Park JY, Kim KW, Kwon HJ, Park MS, Kwon GY, Jun SY, Yu ES. Peritoneal mesotheliomas: clinicopathologic features, CT findings, and differential diagnosis. AJR Am J Roentgenol. 2008;191(3):814-825.

doi pubmed - Takeshima Y, Amatya VJ, Kushitani K, Inai K. A useful antibody panel for differential diagnosis between peritoneal mesothelioma and ovarian serous carcinoma in Japanese cases. Am J Clin Pathol. 2008;130(5):771-779.

doi pubmed - Low RN, Barone RM. Combined diffusion-weighted and gadolinium-enhanced MRI can accurately predict the peritoneal cancer index preoperatively in patients being considered for cytoreductive surgical procedures. Ann Surg Oncol. 2012;19(5):1394-1401.

doi pubmed

This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution Non-Commercial 4.0 International License, which permits unrestricted non-commercial use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited.

Gastroenterology Research is published by Elmer Press Inc.